Transcript

Tara McDowell on Robert Rauschenberg’s Collection, 2002

Robert Rauschenberg

Collection

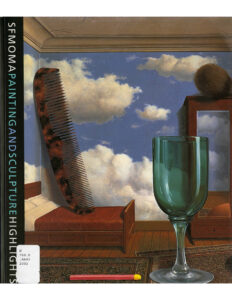

Aptly titled, Robert Rauschenberg’s Collection (1954) presents an array of photographs, fabric scraps, newspapers clippings, wood blocks, paint drips, shapes, colors, and textures jostling with one another and jockeying for position on one vibrant canvas. Scribbled paint strokes blur the punchlines of comics, drips of white paint collide with a thick red line squeezed right from the paint tube, and bits of headlines such as “Dandruff may be the beginning of baldness” jump out amid abstract patches of pink, red, and yellow. Collection is one of the first of a group of works made in the 1950s that Rauschenberg termed “combines,” addressing the quandary of placing such work within more clearly defined media categories such as painting, sculpture, collage, or assemblage. Incorporating elements of each, Rauschenberg’s Collection resonates with the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century practice of gentlemen collectors accumulating objects into a Wunderkammer, or room of marvels. Perhaps not surprisingly, when asked to identify his greatest fear, Rauschenberg responded, “That I might run out of world.”1

Coexisting with the random, improvisatory nature of Collection is an equally strong logical presence. The picture is divided into nine sections—three distinct vertical panels marked by three horizontal bands of pictorial activity—and the image is almost quartered by the intersection of the red and white lines of paint mentioned above. The middle horizontal band holds the crux of accumulated objects, and thus the most activity. The lower horizontal band retains an emphasis on bands of color similar to abstract works by painters such as Morris Louis and a repetitive logic that foreshadows minimalists such as Donald Judd. The upper band of geometric collages of fabric and paint maintains a cool neutrality.

Rauschenberg’s use of found objects and everyday materials in the combines to invade and subvert the pristine nature of the picture plane has both elicited critical attention and influenced a variety of artists, from Joseph Beuys and Andy Warhol to Bruce Nauman and Sigmar Polke. Equally important, however, is his respect for the integrity of the picture plane in these works, a respect that stems from his admiration for and emulation of the generation of Abstract Expressionist painters that came before him, including Willem de Kooning and Clyfford Still. Although the use of banal objects draws inspiration from the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, the improvisatory gestures employed in applying both paint and object to Collection owe much to the generation of “action” painters to which Still and de Kooning belonged. [TM]

1. Rauschenberg, quoted in Robert Rauschenberg and Donald Saff in Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991), p. 179.