primary source

“I Am a Photographer of Attack”

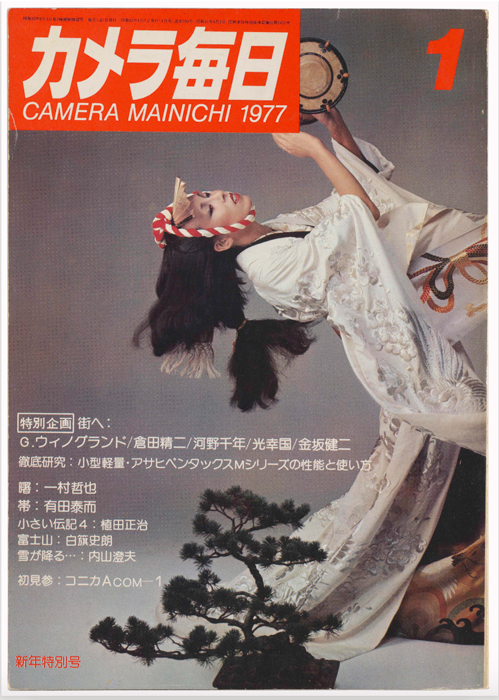

Camera Mainichi

Shoji Yamagishi

- original document

- Japanese

- publication type

- article

- publication date

- 1977

This document file is downloadable in the original Japanese, with the English translation below.

“I Am a Photographer of Attack”

“Toward the City,” special issue, Camera Mainichi (January 1977): 48–52

Shoji Yamagishi Interviews Garry Winogrand: America’s Most Stubborn Photographer

Regardless of its merits or demerits, roughly ten years ago the book Contemporary Photographers[: Toward a Social Landscape], edited by Nathan Lyons, exerted an enormous influence over the Japanese photography scene. It introduced Garry Winogrand—along with Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Danny Lyon, and Duane Michals—as one of the flag bearers of the American photography world. Since then Winogrand has published just two thin, lightly produced books, The Animals and Women Are Beautiful, but he has continued to take photographs with immense dedication.

Last year, in the new year’s special issue “Thinking Photography in New York,” Akira Kokubo published “Two Extremes,” and in the November issue Taeko Tomioka wrote a commentary called “Gaze of Derision: Women Who Look at Women and Men Who Look at Women,” both of which examine Winogrand’s work. This interview follows up on those two essays.

Winogrand teaches photography at the University of Texas at Austin, but I learned that he would be returning to New York, where he once lived. I went to meet him at LaGuardia Airport on the day of his arrival.

Do Not Misunderstand the Works of Diane Arbus

Yamagishi: When I see you or your pictures, I’m led to think about something that a lot of photographers are in the process of losing. For instance, I suspect that the vitality that is at the root of photography is in the snapshot.

Winogrand: What’s meant by the word snapshot is rather ambiguous. I get stuck on that word. Fundamentally, when looking at a photo, no one knows exactly how the photo was taken. Simply by looking at it, I mean. You’ve never seen me while I’m taking pictures, right? It’s completely possible that I set up a tripod and used a view camera to take these photos. (Of course, that’s not the case.) I don’t really understand the word snapshot.

I’m sure you know the photographs of Diane Arbus well. Two lineages have developed under her influence. However, both were born out of a misunderstanding of her work. Her works are masterpieces. No one can deny that, but people misunderstand what makes her work so wonderful. One of those misunderstandings is the assumption that the strength of her work comes from cooperation between photographer and subject. Kind of like in the photographs of Bruce Davidson. East 100th Street, the collection of photos he took in Harlem, is a good example. He was completely influenced by Arbus, but you can tell how thoroughly he misunderstood what Arbus meant to do. He thought the reason her work was great was that she spoke with people before taking their pictures—I’m trying to say that’s a mistake. The other misunderstanding can be found among people like Les Krims—they think that photographic subjects shouldn’t be ordinary. They think that a picture will be great if a photographer takes pictures of things that people would ordinarily turn their eyes away from. If you take a good look at all of Arbus’s work, you’ll realize that the majority of her greatest masterpieces are shots of ordinary people! If you tried to explain why her work is so strong, I am sure you could come up with any number of reasons, but you’d be totally wrong if you thought it was due to the two reasons I’ve just named.

To return to what we were talking about before, it’s not impossible that Arbus just dropped in at someone’s house, took a quick shot, and hightailed it out. Simply by looking at her photographs, you can’t tell the circumstances of how they were taken. There’s also no way to determine whether or not she knew her subjects well. Photographs don’t have mouths! The question of what happened between subject and photographer while shooting has no relationship to the finished photo itself. I think descriptions like it’s a snapshot or the photograph was taken after seeking permission have no meaning whatsoever when it comes to the picture itself.

Putting It in a White Frame Does Look Elegant, But . . .

Yamagishi: Since the big visual magazines like Life and Look went under, interest in original prints seems to have increased. There are also more books of photography that represent individual perspectives.

Winogrand: Different people have different reasons for taking pictures, and that means we encounter a huge variety of photos. For instance, in Suburbia, Bill Owens starts off with a bunch of boring photographs. He wanted to bring them together somehow, so he gave them the title Suburbia. Now, there’s no reason for the photographer to apologize to viewers about taking boring pictures; a collection emphasizes a particular subject in its own way. All kinds of people take all kinds of photographs with different motives. But there have always been boring photographs—we had them in the past, and we’ve got them now, too. The thing is that now we’ve got more exhibitions and more publications, so we’ve got more opportunities to see them. We live in a world where, if you’ve got sixty photos—doesn’t matter what they’re of—you can give them a theme and publish them as a book. All you need is sixty dull photos! There are lots of opportunities to publish, lots of galleries, lots of art museums all over the country interested in photography—both in collecting and in hosting exhibitions. It wasn’t like that before. That’s why there are so many more opportunities to see boring pictures. Even famous galleries like the Light Gallery and the Witkin Gallery hold shows that last three or four weeks each. They do that all year long. I’m sure you’re aware of this, but how many photos in those photo-filled shows are really great? I mean, is it even possible for a single gallery to have twelve really good exhibitions in a year? No way! But—are you ready for it?—in reality, it’s easy for stupid things like that to happen. It doesn’t matter what the pictures are of. They put them in white frames and hang them on white walls. And presto—you’ve got a neat, tidy photo show all ready to go. The pictures look pleasing to the eye even if they’re boring. And that’s what these galleries exist for. [laughs]

A Photograph Is Something Other than Capturing Reality in the Raw

Yamagishi: Maybe it has to do with the conditions of our managed society, but there are more photographers these days who are well behaved and really understand manners. There are more young people who think of photography as intellectual work having to do with ideas, but what stands out to me, at least, are all the photos that lack vitality.

Winogrand: There are a lot of people who take photos, and there are lots of ordinary, moderate people among them. The act of taking a picture is fundamentally passive, like you’re taking something into yourself. Of course, that’s true of me, too, but I define myself as an active photographer—more positive and aggressive. When I’m taking pictures, I’m not an especially friendly, approachable guy. Be reckless and move forward—it’s best not to care too much.

Lots of people don’t realize that the thing captured in a photo is completely different from the photograph itself. That’s been true ever since Nathan Lyons coined the term social landscape. There’s been a fad for boring pictures—photos of signs, photos that look like Pop art, that sort of thing. People used to believe that if you took a picture of a curious-looking gas station, you would automatically get an interesting photo. But that picture wouldn’t be nearly as interesting as the real thing—the weird gas station itself. Robert Frank’s collection The Americans is a really fantastic piece of work, but there were a lot of people who saw it and misunderstood, thinking that if you take pictures of whatever in its most unusual forms, that will result in great photos. In my opinion, it’s a completely predictable mistake. People make it because they don’t understand that a photograph is completely different from reality. Robert Frank had talent, and that’s how he made The Americans. People misunderstand the work of Diane Arbus in the same way—that’s unsurprising, too. The social landscape—it’s a stupid name, but I’ll use it—has also produced a bunch of nonsense photos. I’ve got some photos that might fall into that territory—there’s that photo of mine of a pig swimming with a lady. It’s not a picture I’m ashamed of, but it isn’t that good, either. But people liked it, so it ended up in the book. Once again, the reason is that people don’t understand the difference between the photograph and reality. They don’t understand that a photograph needs to be something other than raw reality. I think that if I were to compare a bunch of contemporary photographs with the realities they show, in most cases, the realities would be far more interesting.

Note from the interviewer: Several days before this interview, by complete coincidence, I was in a suburb of San Antonio, Texas, at Aquarena Springs, which is rather like the aquarium in Enoshima, when I happened to see a show in which women in bathing suits fed milk to pigs underwater. I hadn’t remembered Winogrand’s picture, which I must have seen multiple times, but when he mentioned it in this interview, I immediately remembered and understood what he was trying to say.

It’s Fine to Take Nothing but Boring Photographs

Yamagishi: Camera Mainichi has a page called “Album ’77” that is dedicated to pictures sent in by the public, so every month, I come into direct contact with more than two hundred pieces. I feel like most are static and don’t show much ambition.

Winogrand: It’s been like that for ages, but the reason that we get even more of those—how shall I put it?—“quiet” photos nowadays is, as I’ve been saying all along, because there’ve been more opportunities in general to show photos in recent years. But we had that kind of photo even way back in the day.

Ultimately, you can look at any trend in photography and find photos that are bad or boring or whatever. In the performing arts, there are different genres and different types of viewers. There are good shows and bad shows. You’ll never completely get rid of boring work. That’s life. Imagine you’ve got four restaurants in your neighborhood. Even if they serve the same things at the same prices, you can rank the restaurants from one to four based on how good the food tastes. But, you know, go into every restaurant, and you’ll still find customers.

Yamagishi: So among those restaurants and their respective chefs with their skills, where would you expect to see yourself?

Winogrand: [laughs] Of course, I would be the most outstanding restaurant! [laughs] I’m not even joking, because that’s life. But even if all you take are boring pictures, there’s no reason to stop. You’re not harming anything. It’s fine to take pictures as long as you’re having fun doing it. Of course, it’s a whole different ball of wax if you want to hold a big exhibition in some big place—yeah, I do empathize with those people. Still, it’s crazy if you take a single picture and start thinking ahead, hoping that everyone will recognize it as a masterpiece.

Seven Thousand Photographs in a Solo Exhibition

Yamagishi: I hear that the Museum of Modern Art [(MoMA)] in New York is planning to hold a solo exhibition of your work soon. John Szarkowski showed me a mountain of your photographs piled on a shelf.

Winogrand: Right now I’ve got seven thousand—all provisional prints—entrusted to MoMA. That’s right. That’s just because I take so many pictures. I love it! [laughs] Szarkowski got scared, so he foisted the job of serving as director for my show on Tod Papageorge. [laughs]

Yamagishi: Between the time I met you at LaGuardia, a little while ago, and when we reached this apartment, you took four or five photos out the window of the car. You’re tough, curious—just like I’d imagined. You know, that’s why I felt, I’ll start by asking this guy about the “snapshot”!

Winogrand: Of course, people find all sorts of meanings in everything, in every picture, but when I’m taking pictures, I don’t worry about that sort of thing. My book The Animals started when I was taking my kid to the zoo and started taking lots of pictures. It was only after I saw the developed pictures that I thought they looked like they had potential. Do you remember the picture in there that’s got a rhino with a wounded horn in one corner and a black man in the other? When I took that, the real circumstances weren’t mysterious or anything, but it’s a whole different story when you see it as a picture.

I like zoos, so I used to go to them a lot, but it wasn’t like I went there trying to find meaning in scenes of real, daily life. It was when I saw the pictures for the first time that I noticed I could see something of interest in them. Later I went through the place taking pictures. My way of taking pictures is to go ahead and take them without looking at reality. You realize that when you look at the pictures themselves. I’ve got a picture of a woman reading a newspaper in front of a shop over here, while a man is approaching from the other direction. The picture is a lot more interesting than the real-life scene. Of course, the reason I clicked the shutter was because it was an interesting scene, but the photograph turns into something that was more than a record of the conditions that day.

The photograph should be more interesting than reality itself—it should be something outside reality—but the real problem is that our society is overflowing with pictures for which the exact opposite is true, where reality is more interesting than the picture.

Yamagishi: When I first met you, seven or eight years ago, you were teaching at a university in Chicago. After that I heard you’d moved to Texas, right in the middle of the American Sun Belt. I thought, I guess that makes sense. When influential companies move south, I suppose engineers, researchers, and even artists start to congregate in the South too. But then I heard that you were picking up and moving back to New York, where you were born. What will be the next theme for you here?

Winogrand: Yeah, after leaving Austin, I want to live for a while in my old haunt of New York, but I haven’t decided what I’ll do yet. I don’t even know if I’m going to teach photography somewhere or not. It’ll work out somehow. I’ve managed to live this long already.

Note from the interviewer: After our conversation, I had Winogrand choose the photos that appear in this month’s special issue, “Toward the City.” The photographs he pulled out of the big suitcase he had brought from Texas were so large and varied in tone that even he said, “This might be a little too rough.” He isn’t the type of a person to fuss over things—he’ll quickly say what he has to say and then move on. As he laid the pieces out in front of him, however, I couldn’t help but sense a certain point of view. They had a certain appeal. Seven years ago, when I first met him, I slipped in a question about who had been the one to come up with the words social landscape in the subtitle of the book Contemporary Photographers. His response was short and quick: “That was something Nathan, the editor, came up with to tie the work together.” This time once again, Winogrand, who happens to have been born the same year as me, in 1928, exuded from his sturdy frame the same self-confidence as a practitioner—a confidence that most of us would find enviable.