primary source

“A Symposium: Contemporary Photography—On ‘Everyday Sceneries’”

Camera Mainichi

Camera Mainichi, editor

- original document

- Japanese

- publication type

- article

- publication date

- 1968

This document file is downloadable in the original Japanese, with the English translation below.

“A Symposium: Contemporary Photography—On ‘Everyday Sceneries’”

Camera Mainichi (June 1968): 15–22 (excerpts)

Keynote reports: Kiyoji Otsuji (photographer), Seiichi Horiuchi (critic)

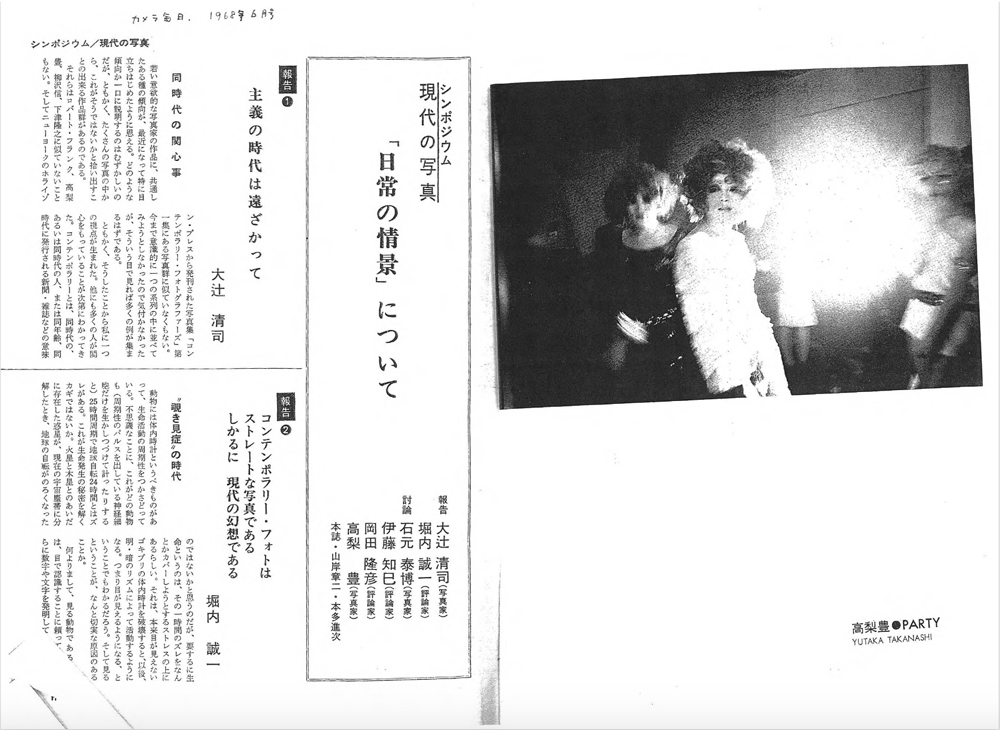

Roundtable discussants: Yasuhiro Ishimoto (photographer), Tomomi Ito (critic), Takahiko Okada (critic), Yutaka Takanashi (photographer)

Roundtable moderators from Camera Mainichi: Shoji Yamagishi, Shinji Honda

Keynote Report 1: Beyond the Era of “-isms”

Kiyoji Otsuji

Contemporary Concerns

I think that recently there has been a common tendency in works by young, ambitious photographers. It may be difficult to pin down in simple words, but considering the many photographs I am seeing these days, I would say that there is certainly something happening at the moment.

It reminds me of works by Robert Frank, Yutaka Takanashi, Shin Yanagisawa, and Takayuki Shimozu. Or, for instance, the photographers included in the first volume of Contemporary Photographers[: Toward a Social Landscape] that was published by Horizon Press in New York. I have not yet consciously tried to align them with regard to style, and therefore my ideas may not yet be articulate, but I assume it will soon become possible to consider them in such a way.

I’ve come to think about it this way, and many people will probably agree: To be called “contemporary,” it is important that things are from the same era, or rather, that the people involved are from the same era. Alternatively, it refers to people who are of the same age, or newspapers and magazines that are published in the same era. That is to say, “same era/same time” is what links things that one feels passionate about, and which one subjects to a similar methodology when capturing them on film. This is how photography books such as Contemporary Photographers came into being and why the term “contemporary” is used in the title. . . .

But what claims are made by these photographs that I would tentatively like to call konpora [short form of kontenporari (contemporary)]? What is apparent so far is that they do not show any clear logic that would aim to establish a new “-ism.” We probably have to consider their approach as something that emerged quite naturally and spontaneously for each of the individual photographers. Their photographs were born at the intersection of the photographers’ methods and their interests in the external world. Of course, we could say this about any photographer. But what distinguishes the konpora photographers is this shared approach in particular, as well as a shared passion for the external world that we rarely witness otherwise. And this is also where the main points of interest of konpora photography are found. It is as if by tacit common consent such tendencies, little by little, have begun to sprout all over the world.

Plain and Simple Methods and Subjects

. . . Let me consider a few characteristics that are conspicuous in these photographs. One is a certain devotion to the mundane and commonplace, combined with a seeming lack of intentionality. These photographers do not bother about events or things that are considered remarkable in a conventional sense. Indeed, they avoid them. Even when they do photograph objects that seem extraordinary, they never accentuate them. They quietly embed them in commonplace situations in such a manner that only those looking attentively might take notice of them. The camera takes a step back, giving room to expansive spaces wherein the extraordinary coexists with the ordinary. They do not attempt to leap out at the viewer with a loud and assertive style, like many other photographs. One suspects that their strategy is to attract attention precisely by bringing the absence of such assertiveness to the fore. It is a bit of a hippie attitude, to my mind.

Man Overtaken by Things

. . . There was a turning point [in human history] when the culture of things began to develop more quickly than humans could follow. I tend to think that from the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century there was still some sort of harmony between man and the material world. But those good old days were not to last. Of course, man tried to keep up the pace, and scientists and specialists devoted their full efforts to their respective fields—not to mention nonspecialized fields in which it also takes time and devotion to maintain the pace of acceleration.

New things and gadgets appear with ever-increasing frequency. This has an effect on people’s values. Developments in transportation and telecommunication have resulted in drastic changes in the ways we think about time and space. The emergence of the computer has changed the world of business. New types of weapons have had devastating effects on the idea of human solidarity. The ideas of love and affection are being replaced by notions of psychology, physiology, and chromosomes. There is an abysmal dimension to such a confusion of values that may easily lead to unforeseeable consequences. We try to detect a common underlying principle in the chaos, but the confusion just seems to be gaining in magnitude.

Practicing artists of today are not given the time anymore to try to make sense of the current confusion. One does not try anymore to find reason in our unsteady, shifting values.

Gaining a Foothold in Chaos

Structures that once seemed sturdy are now looking fragile, and we tend to believe that their collapse is immanent. There is an overall sense of distrust and doubt about things that were once regarded as certainties. Structures that are plain and simple therefore seem to contain the most trustworthy principles. In this age of doubt, our admiration for the elemental is thus growing stronger. It is for this reason that mundane, seemingly immutable phenomena have become preferred subject matter in photography. Konpora photography takes a derisive stance toward the overly staged and pretentious. It tends to be much more introspective. . . .

Konpora photography is founded on the immediate and sensitive responses of individual photographers to these realities. What they have in common is that they all try to find stable ground in the midst of confusion and chaos. . . .

Keynote Report 2: The Age of Voyeurism

Seiichi Horiuchi

Contemporary Photography Is Straightforward Photography. Therefore, It Is a Modern Illusion.

. . . As our convenient and reliable text culture is giving way to a new emphasis on the visual, we have yet to become fully aware of the important implications of this transition. Many things have already been said about this new visual era and our TV civilization, and there is no need to repeat them here. We are made to continuously watch things that are produced merely for the moment. Hence, the contemporary era is one of voyeurism.

Many who are inclined toward voyeurism behave in a fairly passive manner. Then there are those who like to be watched and those who take a more active stance in general. It is a popular affliction nowadays, and it certainly fits the pattern of our present era. But the true voyeur sees through the awkward spectacle. The true voyeur also rejects superficial gratification, because he is in search of the genuine. He prefers lies in full color to the monotone uniformity of truthful grains of sand. He believes in fantasy in the Old Greek sense of the word: “that which can be seen by the eyes.” The genuine voyeur, therefore, is one who seeks truth.

On the Photographs Included in This Issue

. . . In contemporary photography there exists a range of more painterly approaches (including collage, multiple exposures, or solarization effects such as those used by Man Ray) that are regarded as part of the field of fine art and thus have already found their own audiences and venues. Even on a purely pragmatic level, such approaches exert influence. But straightforward photographs that seek to capture casual, everyday situations in the most direct manner are not mere illustrations of reality. These artists have internalized the insistence on their own autonomy.

And in fact, the photography journals are already beginning to embrace these nonconformists.

Roundtable Discussion: Getting to the Core of Photographic Expression

Rejection of Staged Photography

Camera Mainichi: As all of you have just heard the two keynote reports, I would like Mr. Takanashi to speak first about why this type of photography has become so prevalent among young photographers. What is your personal experience in this regard?

Takanashi: First of all, young photographers are questioning the meaning of staged photography. A camera does not provide the emotional nuance of language. It just captures things as they are. Regardless of who releases the shutter, the photograph will turn out the same. Therefore, photographers have begun to experiment with various techniques, such as manipulating the tonality or distorting the image, in order to express emotion and thought—in other words, to make a photograph one’s own unique work of art. But if you overdo this, the resulting images become all about the presence of the photographer and will still be lacking in the things that matter. Pictures that are made to be works of art, or tableaux of a sort, do not “breathe” as photographs, in the sense of being true to their medium. I think what young photographers are trying to do is to return to the basic functionality of photography, its most primitive qualities, and to use the inherent strengths of such primitive photography to express themselves. Therefore, this type of photography often concentrates on fleeting, utterly unpretentious subject matter. But in my opinion, that is also what lends these images their true complexity.

Ito: Mr. Otsuji, who teaches students at the university, has been quite shocked by this phenomenon and hence has begun to actively explore it. I think this is what finally led to the assessments given today in his keynote report. Many of us had similar moments in the past. There was something of it already in the photographs of Mr. Ishimoto, and it continued in the works of Shomei Tomatsu and Yutaka Takanashi. This phenomenon seems to have come to our attention all of a sudden, but I believe it relates strongly to the problem of “sharpness” that Mr. Otsuji has already been talking about in his classes for the past two or three years. Though, admittedly, I haven’t attended his lectures in person yet.

Ishimoto: I think the problem of “sharpness,” as Mr. Otsuji describes it, encompasses the various elements that comprise a photograph, including decisions surrounding shutter speed, image processing, and, ultimately, the meaning that one attributes to a photograph. This word implies a new approach that synthesizes such elements, which have been treated separately until now.

Ito: In a sense, Otsuji’s way of dealing with the phenomenon just brought to plain light a strong undercurrent that people had not yet taken any notice of.

Okada: Continuing from Mr. Takanashi’s earlier point, I think there was a moment in photojournalism when perhaps too much attention was paid to the idea of documentary photography as the ultimate embodiment of modern photography. In any case, the possibilities have all been tested, and from the point of view of the younger generation it now seems impossible to continue any further in this direction. On the other end of the spectrum, there is the excessively staged approach of so-called “art photography” and of commercial photography, which for the most part quickly leads photographers to fall into a kind of mannerism. The younger generation is keenly aware of these tendencies and sees itself as being caught somewhere in the middle. It is a natural way out of this dilemma for them to focus on that which is peculiar to photography, that which cannot be captured otherwise, and to build their expressive means around such inherent qualities of the medium.

Capturing the Beauty of the Everyday

Ishimoto: What do you think about contemporary photography’s relationship to Pop art?

. . .

Okada: There are many people active in Pop art; one cannot discuss them all in a one-dimensional way. But I think Pop is interesting because it is so nonparadoxical. For instance, they [Pop artists] will depict completely ordinary scenes in a seemingly serious manner, full of beauty and poetry, but this is literally all they do. They are absorbed in this approach without ever bothering with the high-brow topics and intellectual pretensions of conventional fine art, not to speak of any articulate criticism of their artistic forebears.

Takanashi: But at the root of it, there is clearly something that they’re rejecting, isn’t there?

Okada: I do not think that is quite the case. What about your own work, Mr. Takanashi? For instance, Tokyoites, in the January issue (Camera Mainichi, 1966)?

Takanashi: I think that one is wonderfully good. By that, I mean I usually do not photograph objects because I like them. I constantly think, “I cannot take this, I cannot take that.” That is the way I work. For instance, I cannot photograph girls in the polished manner Hajime Sawatari does. I envy him, but I also know that I am different. It would be a poor artistic statement to say that I don’t take “beautiful” pictures and that I intentionally make them disagreeable—unpleasant to look at—only to express the opinion that we should all reject this [Sawatari’s] style. But the more beautiful something appears on the surface, the more wretched it might really be, is how I tend to think about and approach those things. . . .

Holding onto the Single Photograph versus the Photo Series

Camera Mainichi: Mr. Horiuchi’s keynote report mentioned a new approach to the single photograph, but wouldn’t [Kuniko] Sato’s Rooftop People rather constitute a new type of photo series?

Takanashi: Sato’s work does not follow the usual narrative mode of a photo series; she actually holds onto the single photograph. She doesn’t follow photojournalistic conventions but juxtaposes individual photographs against one another in order to explore the communicative potential of such an approach. . . . Journalistic photographers tend to compose montages based on one-point perspectival imagery. They see their subject matter in terms of a narrative pattern of introduction, development, climax, and resolution, very similar to that which is often practiced in literature or poetry. But things have developed in such a manner that this montage approach is no longer sufficient to reflect our present realities. Even the word “collage” might not be fully appropriate here. Our reality is one in which the conventional narrative pattern has ceased to make sense, or, rather, one could also say that such patterns actively need to be broken up or interrupted. Ms. Sato’s work attempts to express these ideas. We also find this aspect of intentional discontinuity in Mr. Shimozu’s two photographs. Say I were to photograph a zoo. There is probably some appropriate way in which one would usually do this. But I wouldn’t use it. I would plunge myself into that space, see how I really felt about it, and try to show it in a manner that I would consider true to myself. . . . I tend to hold onto single photographs, one shot at a time. When I take a photograph, I cling to the idea that I want to have my worldview projected into this one, single image. . . .

Okada: As Mr. Takanashi has said, the one-point perspective heretofore typical in photography assumed the photographer as the center from which the visual space gradually unfolded. We now understand that instead of reflecting reality, taking a photograph in this way meant creating an illusion. . . .

Ito: And I might add that the fundamental concern of konpora photography remains the single photograph.

Different Ways of Interpreting Photographs

Okada: I’m struck by two conspicuous tendencies. One reminds me of the photo studios of the old days, where the people being photographed look directly into the camera, as if to commemorate just the present moment—much the way amateur photographers and beginners have their subjects pose artificially. . . . The other tendency is what Mr. Ishimoto has already practiced for quite a while, but which became really obvious in his series Chicago. It is the tendency to capture images that do not show anything real, that are fiction. For instance, Ms. Sato’s photograph . . . of an image on a TV screen. The contrast between these two approaches really preoccupies me. Concerning the old photo studio approach, it appears to me as if these photographers have given up from the start the notion of capturing any actual reality. They produce photographic fictions into which they unconsciously project their own ideas. The other tendency, where photographers shoot images as if they were reflections on a television screen, it is a more complex procedure, but I am under the impression that these photographers want to seriously inquire into what it is that defines photography. . . .

Ito: Speaking from my perspective, I do not think about the tableau approach at all. Rather, that is what I most resist. For instance, the reason I find Sato’s [other] photograph . . . interesting is that as a Japanese viewer, I have certain interests in Tokyo as it exists today. Tokyo no doubt is a symbol of Japan as a developed capitalist country, but to the same degree Tokyo smells of poverty—from building to building, the windows, the alleyways—regardless of how much capital there is, of whether Yawata Steel and Fuji Steel have merged, of whether the automobile industry here is undergoing monopolization, or of how Japan and the U.S. compete internationally for monopolies. These things go through my mind when looking at this image. . . .

Okada: Your way of looking is in fact a way of reading, isn’t it? You are turning everything into words. . . .

Ito: I have talked about how I felt—that is, the connection between myself as an individual and this photograph. How about you?

Okada: . . . I think herein lies what’s at stake for the photographers of our era, those who have made a decision not to paint or make films but to take photographs. I believe that your thinking about photography is based on very articulate and idealistic notions, whereas I would like to approach photography in a more lighthearted manner.

Reality without Drama

Takanashi: Mr. Ito’s idea of good photography amounts to drama, in the traditional sense of the word. But subsuming photography under the preexisting notion of drama is to say that it does not offer the viewer any new means of perception. When Mr. Ishimoto returned to Japan, he asked me, “Takanashi, I saw a black man in Chicago who drove a tractor while smoking cigarettes. Should I have photographed him in such a way that he ‘appeared’ to be working?” The common idea of the drama called “work” would be to show a man with sweat running down his forehead. Mr. Ishimoto keenly noticed this divergence between reality and drama. Back then, I simply told him to take pictures naturally, unaffectedly. . . .

Ishimoto: That is true. Those photographs of mine were certainly made to create drama. That’s why the whole approach feels so outdated to me now. Drama means the production of monuments or heroes. But those things no longer exist in the present era. In the present era, everyone is a hero or a star. Young people intuitively sense this, and that is why this type of photography came into being.

Takanashi: I was really shocked when I saw Mr. Ishimoto’s Chicago series in the exhibition at the Takashimaya department store. . . . Two ordinary people were simply shown passing each other on the street. That was what shocked me so much—namely, that he was getting away with presenting such an ordinary scene as a work of art of his own. It inspired me. . . .

Ito: Our discussion is slowly turning into konpora as well.

Okada: We are not studying modernity per se, which is also different from drama. It is rather that a particular type of action is in the process of realizing itself. Mr. Ishimoto became aware of this early on—that is one of his true achievements.

Ito: Mr. Ishimoto, before you were talking about drama, Mr. Takanashi equated it with preconceived ideas. But the idea of drama that you are using now seems to be different.

Ishimoto: Not really. I think it is quite the same. Drama in the old sense was rather melodramatic; the drama we are talking about now just has a somewhat dryer quality.

Reflections on Ourselves

Camera Mainichi: Our symposium is not intended to produce any final conclusions, but we would like to ask everyone at the roundtable to conclude with a word about your most pressing concerns or thoughts at the moment.

Takanashi: Things are becoming so multilayered and diverse that I wonder if there is any good at all in mechanically lining them up, one after another. Toshio Matsumoto showed his film We Are All Crazy Clowns recently, at the 1968 Universal Exposition. He brought three projectors and projected images from them simultaneously, because he is interested in this aspect of layers and overlap. But I thought this only produced a descriptive result and was no more than a reflection of certain stereotypes about reality. I missed any real attempt to synthesize these things and to define his own position toward that reality. And I think we have the same kinds of problems in photography.

Ito: By which I think you mean that the approach of contemporary photography is, or should be, to earnestly question once more what photography means to those of us who are taking pictures. I’m not sure to what extent each artist is actually doing this. It is important to raise these problems, regardless of whether one is dealing with cause or effect, or with the photographer’s sensual responses or intuitive reactions. I previously tended to ignore photographers. There is a certain haughtiness in the way they try to guard what they consider their exclusive rights. For instance, when [Louis] Daguerre presented his first photograph to the French parliament, he asked for a state pension as a reward for his achievement. Everyone was shocked by that photograph of stones and pebbles. Moreover, it was stones inside clear water. This must have amazed some of the lawmakers, to the extent that they agreed to give Daguerre his pension. In any case, I’m bringing this up because I think it is not just an amusing anecdote from the distant past. There is a similar kind of haughtiness, even arrogance, in Tomatsu compiling his anarchic photographs into a book that he calls Japan—that is, picking up as subject matter whatever pleases him and giving the result the title Japan!

Okada: I think it’s sad that photographers do not more actively try to construct their own worlds and let viewers respond to them. Such worlds should be shown to the audience with real confidence. If Tomatsu’s series Japan is arrogant, I actually wish that many more people with a variety of approaches would dare to have such arrogance.

Ishimoto: I think it is quite all right for “Japan” to be shown in photography as a sort of cancer. When the next generation of photographers appears, they will be puzzled, and in consequence they will try to find a new and different approach once again.

Ito: I do obsess about the idea of newness. I feel strongly about continuously calling things into question and revising or changing them.

Ishimoto: Tomatsu is Tomatsu, so he sees Japan in his own, new way. Mr. Ito also has his own, unique ideas. It is different for everyone, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that everything of today is old and outdated and that what belongs to tomorrow is always new.

Ito: I absolutely agree.

Camera Mainichi: At this point, we thank you all for your participation.