Consuelo Delesseps Kanaga (1894–1978), whose work was included in seminal photography exhibitions including the inaugural Group f.64 show at the de Young Museum and Edward Steichen’s Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art, and who counted some of her era’s most renowned photographers among her inner circle, is finally getting a much-deserved West Coast show.

Kanaga lived a fascinating life, coming into photography just as the medium was gaining ground creatively and as a documentary medium. She grew up in bucolic pre- Golden Gate Bridge Marin, before moving to San Francisco. In 1915, at the age of 21, Kanaga became a reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle—a remarkable move for a woman at that time, but only the first of her many personal and professional leaps. “She wrote on a range of topics, from ballroom dancing to women in the workplace to the bison in Golden Gate Park,” describes Shana Lopes, assistant curator of photography, who organized this San Francisco presentation and has an essay in the catalogue. By 1918, Kanaga was a staff photographer.

The city was in a state of incredible expansion, still rebuilding after the 1906 earthquake while simultaneously becoming a global financial and trade center. The 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition, held in the Marina to celebrate the opening of the canal, welcomed 18 million visitors in one year. San Francisco was also a thriving creative center. “The Bay Area—especially during the first half of the 20th century—was extremely important to the history of photography and Modernism in general,” says Lopes, “and the photographic community was close-knit.” Kanaga had become friendly with Dorothea Lange, who invited her to join the California Camera Club, where she had access to a darkroom, and members often showed their work. “The California Camera Club had a larger membership than the photo clubs Alfred Stieglitz was running in New York at the time,” says Delphine Sims, assistant curator of photography, who provided curatorial support for this retrospective. “And the number of women photographers was pretty fantastic.”

Kanaga, like Lange, saw photography as both creative expression and a tool of communication to highlight groups that were otherwise invisible. “They both believed that if people saw enough photographs of marginalized individuals, of the workers’ fight, of poverty, it could inspire change,” says Lopes. “And both tried to express humanity or the human condition in a moving way.”

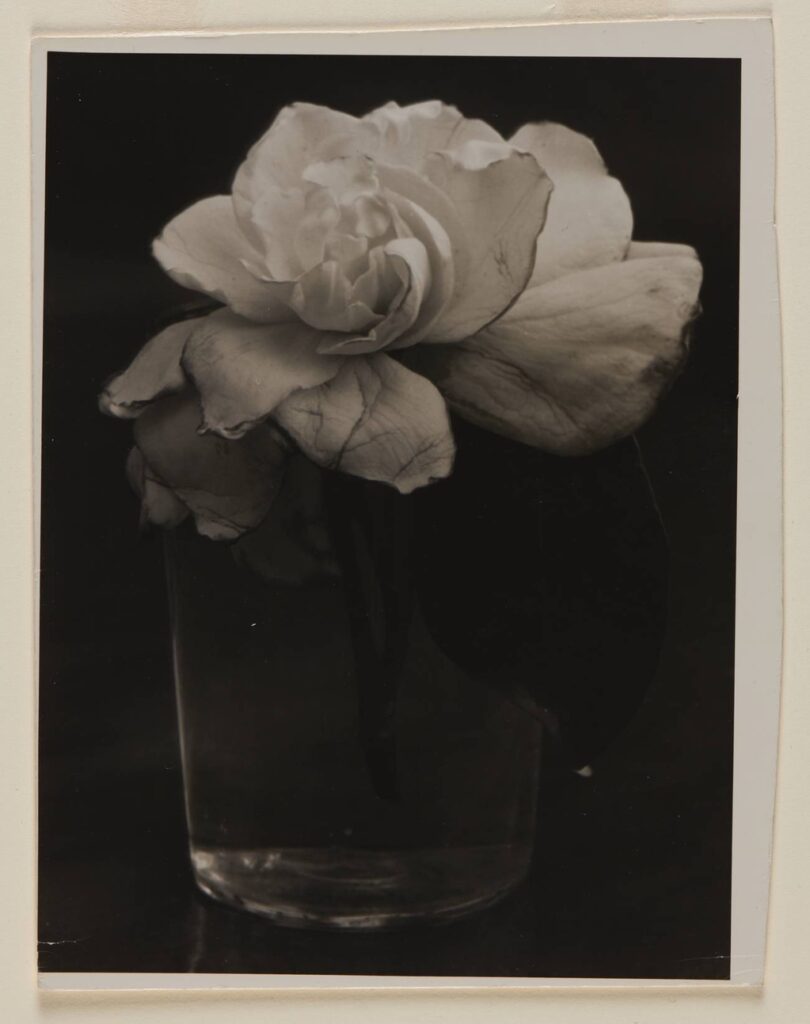

“Her work fused art and politics. She wanted to visualize the human condition in all its complexities, and it gave her work unmistakable gravity. But she also photographed the everyday world around her, finding beauty in the small details—the gardenia that is wilting, or the city street at the end of the day when the shadows grow long.”

In the 1920s, Kanaga began photographing the Bay Area’s Black communities, including moving portraits of its workers, and their home life and culture. Several of her graceful images of Eluard Luchell McDaniel, a young man she’d hired as a handyman who became a close friend and frequent subject, are included in the exhibition. But those images were more about form than social action, says Sims.

“At that time, she tried to capture the beauty of McDaniel’s face, the lighting, and so on. But as she moves forward and goes to the South to photograph the agricultural workers, the work takes on a more documentary slant and features images of Black labor activism.”

Kanaga’s creative career had to navigate around her rather unorthodox (for the time) personal life. She married and divorced three times, moved frequently, and traveled constantly. She was often the primary breadwinner, working as a portrait photographer. After moving to New York City in 1922 to work for the New York American newspaper, she befriended photography’s éminence grise, Alfred Stieglitz, and through their friendship, her work moved to a more artistic style.

In 1932, Kanaga was invited to participate in the inaugural Group f.64 exhibition at the de Young. “The seven original members, who were also pivotal to the creation of SFMOMA’s collection, included Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, and Edward Weston, all of whom lived in the Bay Area at the time,” says Lopes. While she had four pieces in the landmark show, Kanaga never officially became part of the group. “The f.64 artists were interested in the idea of straight photography that celebrated the medium’s capacity to present the world ‘as it is,’” says Lopes. Kanaga’s work was more emotional, and socially engaged; for example, during the 1934 West Coast longshoremen’s strike, she went to the docks, capturing images of fights, police brutality, and property destruction.

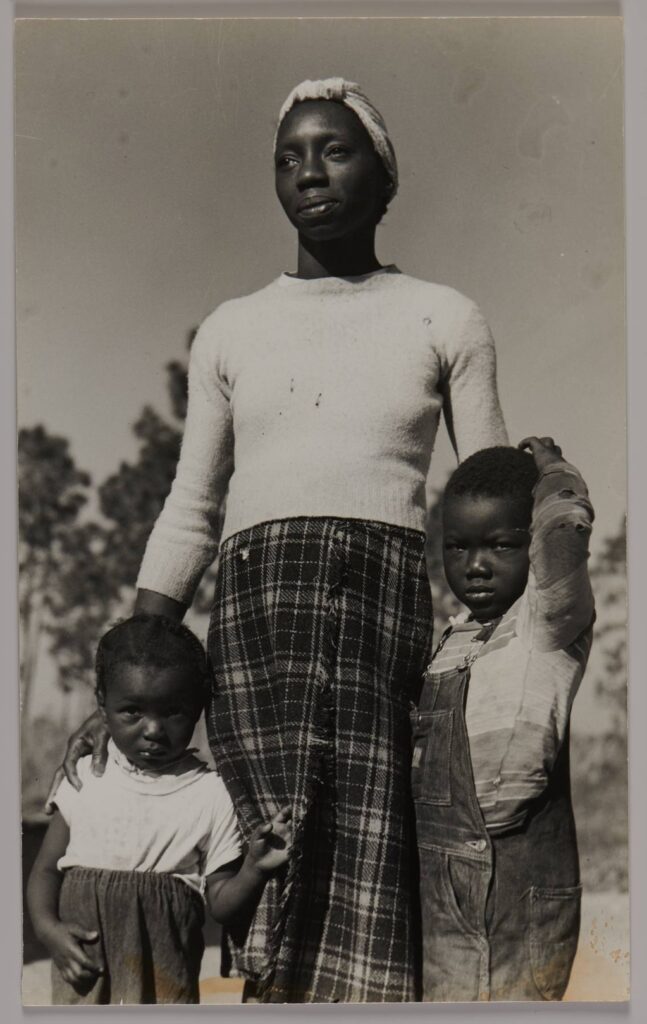

Her most recognizable work combines her skill in both form and subject. Kanaga was in residence at an artists’ retreat in Florida, documenting Black agricultural workers in the reclaimed swamplands of the area, when she took a photo of a young Black woman with her two children. Edward Steichen selected the image, titled She is a Tree of Life, for his 1955 blockbuster MoMA exhibition The Family of Man. In 1993, the Brooklyn Museum organized the first retrospective of Kanaga’s work, largely drawn from a collection of 2,000 negatives and 340 prints left to the museum. It also organized this exhibition.

“She was way ahead of her time. Generally if you use the word unconventional, you mean someone who breaks the rules—she had no rules.”

Given her early work, rich cultural milieu, and a lifestyle that was an anomaly for her time, it’s surprising Kanaga isn’t more of an icon, artistically and personally. “Gender inequality, social norms, and class constrained Kanaga’s ability to fully commit to her art,” says Lopes. “She worked various jobs to support herself, leaving only weekends to pursue photography. This is perhaps one reason why there is still much mystery around her life and work. In an interview from the early 1970s, she said ‘Most of my early work has been lost or spoiled or disregarded because I’ve traveled around so often.’”

Years later, Lange said, “she was way ahead of her time. Generally if you use the word unconventional, you mean someone who breaks the rules—she had no rules.”

“Her work fused art and politics,” says Lopes. “She wanted to visualize the human condition in all its complexities, and it gave her work unmistakable gravity. But she also photographed the everyday world around her, finding beauty in the small details—the gardenia that is wilting, or the city street at the end of the day when the shadows grow long.”