Wolfgang Tillmans has engaged the world through photography for over 30 years, working with an uncommon openness, sensitivity, and desire for human connection. Throughout his career, he has explored a wide variety of subjects in various forms: black-and-white photocopies, intimate portraits, still lifes, astronomical observations, cameraless abstractions, videos, and more. This diverse practice is united by Tillmans’s drive to depict the full range of what he encounters — from the mundane and personal to the unusual, ecstatic, and political.

In November, Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear comes to SFMOMA from the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Art Gallery of Ontario. The acclaimed artist’s largest exhibition to date, it brings together hundreds of photographs arranged in constellations that extend from floor to ceiling, alongside video work and installations. This unique mode of presentation embraces the concept of visual democracy, where, as Tillmans puts it, “If one thing matters, everything matters.”

Curator and Head of Photography Erin O’Toole recently spoke with Tillmans ahead of his SFMOMA exhibition.

Erin O’Toole: What are the origins of the exhibition’s title, To look without fear?

Wolfgang Tillmans: For me, an exhibition title doesn’t explain the exhibition, but gives a certain spin or a taste — a point of entry. I felt that for this show, my first full survey retrospective, it needed to be something that fit the whole practice. I’ve said many times in interviews that I want to use my eyes to look without fear — to not be afraid of what information they deliver and to be open about what I see. This process of questioning how we look at things is really at the core of my practice. It is not a given that I am always able to look without fear; it is also a hope that I will be able to do so — and a demand that we, as a society, will be able to do so.

EO’T: What first drew you to photography?

WT: After a succession of trying other media during my teenage years, including making clothes, painting, drawing, and making music, I actually discovered photography as my preferred means of expression last. Photography hadn’t played a role because I come from a family of avid amateur photographers, and what teenager wants to express themselves in the medium that their parents do? But I had a great awareness of photography in newspapers, and I was drawn to record covers from an early age. Then, when I was 18, I went to the local copy shop and made a fanzine with collaged images and my own lyrics. They had a new machine — the first digital laser copier — which was able to reproduce photographs in half-tone. I started to experiment with the machine, and a couple of years later, had my first exhibition with those photocopies. I needed more photographs to enlarge for the exhibition, and that’s when I bought a camera. Only after a year or so did I realize that I could speak with the pictures directly, rather than through the distorted and abstracted process that the photocopier made. From then on, I started using photography to talk about almost everything that concerned me. Fortunately, it still feels like it has that potential.

EO’T: You began photographing your queer community very early in your career. Did you see it as a political gesture, or was it just part of your life that you were capturing?

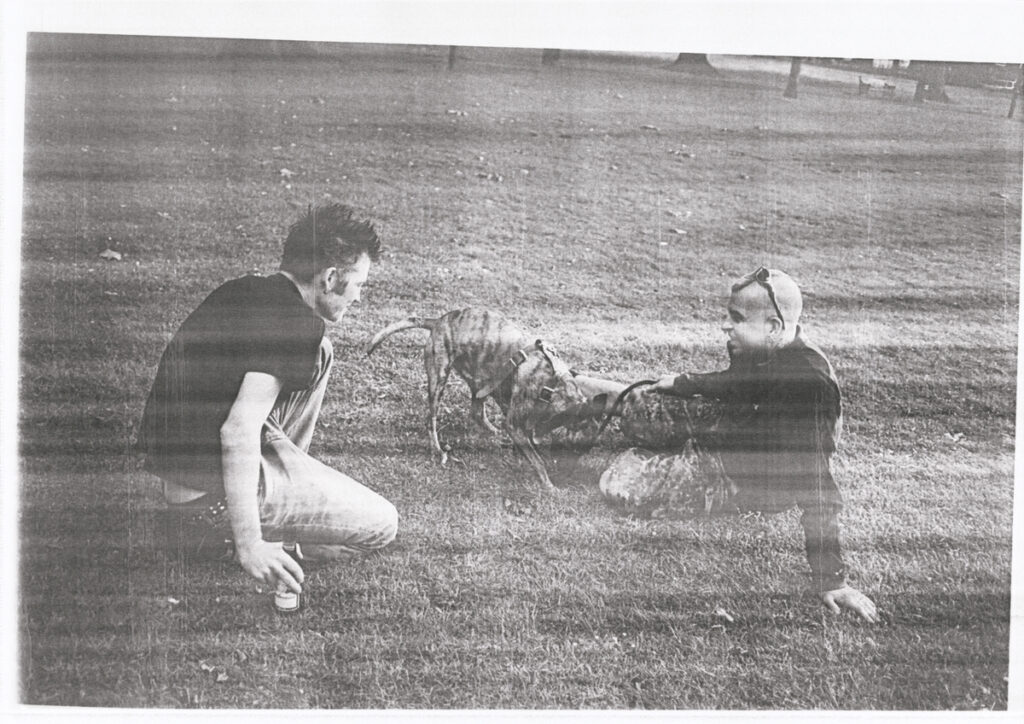

WT: In the early 1990s, when I really started formulating my voice, I was enthused by the increased sense of freedom of expression around one’s sexuality. Post-1980s, this felt like a new beginning — a more aware period that wasn’t as much about what divides us. I wanted to describe the newly emerging relationship people had with their body and sexuality. For example, in the pictures of Alex and Lutz, there is a woman and a man, but they read as somewhat queer images, in the way that the term is not necessarily confined to a definition of sexuality alone. I never wanted to be a gay artist, but I understood the power of my work and of the times that we gradually entered. The early 1990s were very different from the late 1990s — there was a massive shift of acceptance within that decade. The great power of that was that I could operate within a larger audience, rather than speaking to a niche audience. In retrospect, sometimes I have to watch that I am not being shoehorned into simply a queer context.

EO’T: Your photograph The Cock (kiss) from 2002 has been shared online to communicate queer resilience. What was your reaction to seeing the image used in that way?

WT: The picture is a good example of a number of things. I didn’t seek out a gay kiss. It was more a picture I had to take, because I just saw it in front of my eyes at this club night called The Cock at The Ghetto in London. I was a regular, even deejayed there on and off, and felt free to photograph there. At moments, I feel a responsibility to record this as a matter of fact: this happened, this took place. The motivation comes from an awareness that the societal advances and freedoms of expression that I experienced in my lifetime have been achieved relatively recently and constantly remain under threat of being reversed. Maybe this answer circles back to that; the motivation behind the picture was so pure and direct — describing the freedom and energy of a passionate kiss in a nightclub — that this moment could have also happened at the Pulse Nightclub or any other gay, LGBTQ venue.

EO’T: You’ve toggled between representational and abstract work throughout your career. What inspired you to start making cameraless work?

WT: Recognizing that there is photomechanical potential for my expression came through the early photocopies, which were created through an enlargement process that abstracted straight photographs into images that resemble fine-grain drawings. By the late 1990s, I already felt there was an enormous proliferation of image making and a focus on figurative/representational photography, and I felt the need to put a brake on that myself. So, I devised tools that allowed me to draw, technically speaking, with light. Because these images still looked photographic to the eye, they were not primarily considered in the context of painting, even though it may seem that that’s where they’re actually better placed. Freeing them from the context of painting opened the images up to sit freely next to my figurative photographs, and that opened a whole dialogue that activated the camera-made pictures, as well as the other way around, for the last 20 years.

EO’T: Can you talk a little bit about how you first came to install your work in the unique way that you do?

WT: I feel fortunate that I come from a background of having looked at art in museums, either when traveling or in the Rhineland cities [around my hometown]. I also appreciated photographs in magazines and print, and the artists that I first gravitated towards turned out to be almost exclusively artists who transferred photographs from print into painting, like Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, or Robert Rauschenberg. Somehow, I never experienced the barrier that people often feel between high culture and low culture. I just felt that I didn’t need to paint my pictures; I found paper to be valuable enough as a carrier.

Later, when I encountered gallery space, I wanted to use what it offers — what the printed page doesn’t have — which is space and expanse. That’s where leaving the linear hanging line behind became necessary and possible. It was striking to me that the prevailing approach was hanging work in a line and in the same type of frames. I felt the need to explode that, because I didn’t think serially, how photography was often conceived. In these spatial exhibitions, I wanted to express how I look at the world simultaneously. For instance, looking at you right now, I see a portrait; looking at this tabletop, I see a still life; looking out of the window, I see a cityscape; and looking at my knee, I see a sculptural form turned into drapery. I take in these four scenarios and work on them concurrently, without separating them into series. I want to naturally bring them into a room like that.

This installation type I created is always perceived as great freedom, but it has rigor underneath that supports it. I stick to four industrially determined print sizes: 12×16 inch, 20×24 inch, 4×6 inch, and 54 inch, dependent on the paper roll length. Within these rectangles, anything can happen. But the rhythm of these four sizes also produces a language matrix I’ve used for 30 years.

EO’T: This is your first major exhibition in San Francisco. What does it mean to you to show your work here?

WT: It’s very meaningful. Even though I haven’t been to San Francisco as frequently as to Los Angeles or New York, this city has played a large role in my imagination and inspiration since I started listening to pop music and [learning about] the politics and subculture of the 1960s. It was also the first developed gay scene, together with New York, and of course the epicenter of the AIDS crisis.

I visited San Francisco at distinct moments in my life. At 22, just before starting college in England, I experienced the pre-gentrified South of Market neighborhood and walked in on an artist talk by David Salle at the Art Institute on Chestnut Street and watched the students give him a severe grilling. In 1995, I came back for the opening of SFMOMA and the Phoenix Hotel Art Fair, when the art world was still very makeshift and self-made, and again in 2013, for a book project, which I also used as a time to drive through Silicon Valley and try to grasp what Apple actually physically means, which was very little. There was always nature and great romance here: the Golden Gate Bridge, the city’s unique exposed position in the landscape, and even the ever-present threat of earthquakes. I mean, for somebody who comes from a non-earthquake region, it is always a little wild that people just live there and build towers that are 200, 400 meters high. It’s the same in Tokyo or Bogotá. You are living with an ingredient in your life that has quite some amplitude — literally.

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear is on view from November 11, 2023, through March 3, 2024, on Floor 7.

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear is organized by The Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition is organized by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator and Acting Chief Curator of Photography, with Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, and Phil Taylor, former Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Major support for Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear at SFMOMA is provided by the Lisa Stone Pritzker Family Fund. Generous support is provided by The Black Dog Private Foundation, Sakurako and William Fisher, Katie Hall and Tom Knutsen, Nion McEvoy and Leslie Berriman, Kate and Wes Mitchell, and The Sheri and Paul Siegel Exhibition Fund.