Bruce Conner, TAKE THE 5:10 TO DREAMLAND (still), 1977; courtesy Conner Family Trust, San Francisco; © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco

In the 1960s, paying practically nothing, I bought twenty acres in a mountain canyon near Dutch Flat, California.

I built a cabin—no power tools allowed—and used it as a kind of retreat from the rest of my life, which at that time had some issues.

It was so incredibly peaceful there—small waterfalls, the sounds of wind in the trees, various insect buzzings and bird chatterings, blue skies, clouded skies, sun and rain. As I lay on the deck looking upward, I heard the occasional sound of a small prop plane dopplering into the distance.

One afternoon I fell half asleep in this peacefulness and heard for the first time a complete piece of music—my music!—with the same concrete reality of any actual sound. Not knowing enough about my craft, I was helpless to write it down before it vanished. These aural hallucinations have continued ever since, not regularly, but apparently when needed.

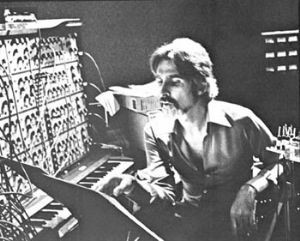

Over a couple of weeks at Different Fur, my recording studio in San Francisco, I tried to reproduce all the natural elements of the Dutch Flat experience using an analog synthesizer, a musical instrument I’ve specialized in, and in this case a modular Moog III. Then, gradually, as the background sounds called to mind the simple melody that was the theme of my half-dream, I added it and then rearranged what was already recorded to make room for the additional melodic element.

It was—and is—a somewhat fragmentary piece of organized sound with no clear beginning or resolution at the end. Also, for reasons I can’t quite say, it was important to me not to use recordings of nature, but to synthesize them instead. I played it for Bruce. After a suspenseful minute or two of silence, he said, “I’d like to have a copy.” Then he asked me what the piece was called. Since I hadn’t really thought of it as a completed composition, I hadn’t given it a name. The piece is five minutes and ten seconds long, so thinking back on the day I heard it for the first time at Dutch Flat, I said, “It’s called ‘Take the 5:10 to Dreamland.’”

Three or four weeks later Bruce came by the studio with his portable 16mm rig—a small flappy screen and a Bell and Howell projector—and screened his film TAKE THE 5:10 TO DREAMLAND.

The images and sound in this work have been abused terribly on their way to your eyes and ears. First, the found footage already had the problems you’d expect—scratches and embedded grime—then add to that the new dirt and dust that accumulated as the footage was run through Bruce’s projector and even as the footage was reprinted in the lab on its way to becoming his film. Sometimes the low frame-rate flicker, scratches, and these various gate artifacts were sufficiently intrusive to become additional compositional elements—as we acknowledged in another of Bruce’s films, TELEVISION ASSASSINATION, where I scored the artifacts and damage as if they were a part of the story being told.

The sound fared no better. The track was originally recorded in stereo with a frequency response nearly flat from 50 cycles to 20,000 cycles, but the limitations of 16mm movie making required that it be reduced to mono. It was also subjected to a supposedly necessary abomination called the “Academy roll-off,” intended to account for the conditions of display in a movie theater. This distorted the soundtrack so severely that even the limitations of 16mm projection didn’t matter because the damage had already been done. The roll-off got rid of the pleasant low rumble of wind and water and did a real number on the insect and bird sounds, smashing them as flat as possible.

But strangely, every time Bruce and I revisited the score in an attempt to restore it to something closer to the original—which we did every few years as new technology emerged—we came away frustrated. What had happened was that the film itself, in an act of agency, had claimed the sound, damaged or not, and this was now “the original soundtrack.” What you’re seeing and hearing is what was intended, although by whom I cannot say.