This fall, visitors to SFMOMA will walk into the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Atrium and immediately encounter two vast abstract canvases, each measuring twenty-seven by thirty-two feet, flanking Snøhetta’s sculptural stairway. Commissioned by the museum, Julie Mehretu’s site-specific diptych is freely accessible to the public. Here we sit down with curator Gary Garrels to discuss the history of the Atrium as a space for new art commissions and the impact Mehretu’s monumental works, HOWL, eon (I, II), will have on the museum and its community.

SFMOMA: In the winter of 1995, when the “old new” SFMOMA opened — the Third Street building designed by Mario Botta, which replaced the old museum in the Veterans Building on Van Ness Avenue — there were these two huge, empty walls flanking either side of the grand staircase in the Atrium. I imagine that the curators felt immediately compelled to fill them with something.

Gary Garrels: Yes, Botta made the staircase a focus as you walked in. It was a grand, black granite form with a relatively small entry point on the ground floor that then ascended up to the bridge under the Oculus. We were indeed aware that those walls would offer an extraordinary opportunity for an artist to do a very major work.

SFMOMA: Were they designed with that in mind?

GG: I don’t know what Botta’s thinking was. But in 1997, I started working on a Sol LeWitt retrospective, and Sol is well known for his wall-scale murals — or “drawings,” as he called them — and so I began discussing a commission for those two walls with him and I was able to secure the financial support from a couple of our trustees to move forward. Sol offered up two proposals, and we accepted one of them. They were executed at the time of the retrospective, in early 2000.

Footage of the installation of Sol LeWitt’s monumental Wall Drawing #935: Color bands in four directions and Wall Drawing #936: Color arcs in four directions (both 1999) in SFMOMA’s atrium.

SFMOMA: The work had very bold bands of color that made the walls feel like a cube or a box.

GG: And people almost immediately began to regard them as integral to the building. Everyone was so delighted with them that Phyllis Wattis, one of our wonderful patrons at the time, gave us the money to make them a part of the collection permanently. They stayed up for five or six years.

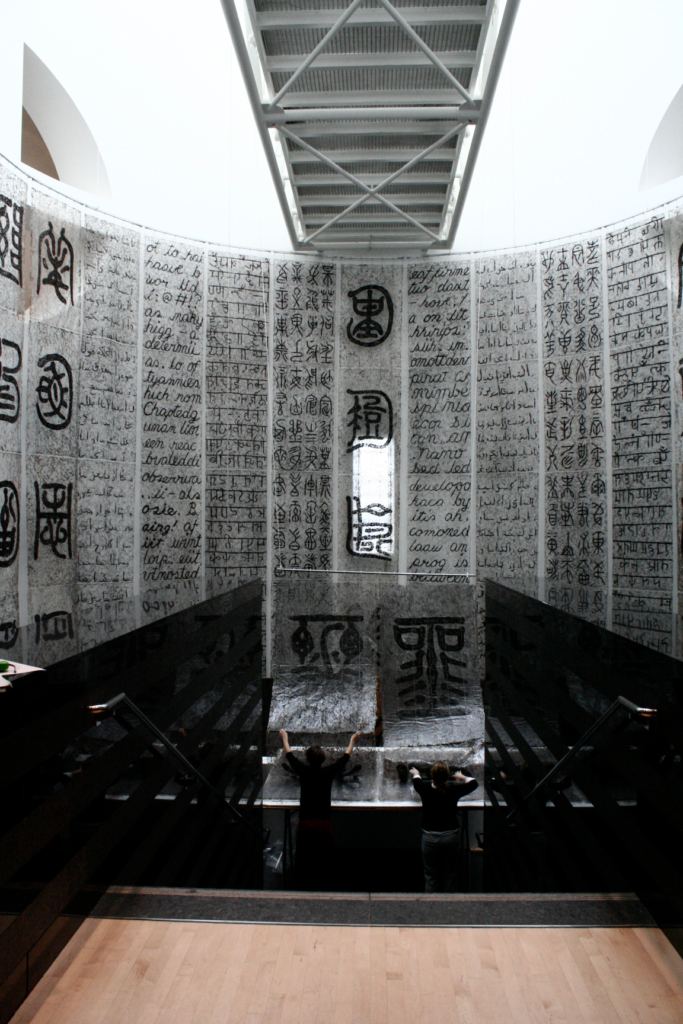

In the meantime, we started using the Atrium space for other kinds of installations. On the occasion of Inside Out: New Chinese Art in 1999, Wenda Gu installed very large hanging panels with designs of woven human hair. At that time, wonderful supporters of the museum named Kent and Vicki Logan were deeply interested in Chinese contemporary art, and they gave us the money to move forward with that commission.

Gu Wenda, united nations--babel of the millennium, 1997; Collection SFMOMA; Gift of the artist; © Gu Wenda

SFMOMA: So those pieces were designed to utilize the space as opposed to the two walls.

GG: Right. And I suppose the Chinese works led to the later work by Olafur Eliasson on the occasion of his retrospective in 2007, Take Your Time. That show included a sculptural piece, a kind of glass tunnel, commissioned for the bridge that crosses over the Atrium into the Oculus, and in the Atrium itself there was a moving fan sculpture that spun and floated through the space. It was absolutely wonderful.

Olafur Eliasson's One-way colour tunnel (2007) now back on view in Contemporary Optics

SFMOMA: What happened to the walls when the LeWitt murals were eventually de-installed?

GG: In 2008 we approached Kerry James Marshall about making new works for those walls. I had done a show here with Kerry James in the 1990s, so we already had a wonderful relationship of long standing. He decided he wanted to do something in dialogue with San Francisco’s venerable Mission mural tradition. He began discussions with Precita Eyes and came up with a plan to create views of the plantations of George Washington (Mount Vernon) and Thomas Jefferson (Monticello), but with black figures inserted. The intent was to point to the presence of black Americans on the plantations, while highlighting their absence from public history. The murals were fabulous.

Photo: Winni Wintermeyer

SFMOMA: And those were up for two years?

GG: Yes, and I have to say, I think it broke everyone’s hearts when they were eventually painted over. With the LeWitts, because of the nature of the work, they can be redone by trained painters anywhere in the museum. But with the Kerry James Marshall works, those were unique, original works of art on the wall, and once they were painted over, they were gone.

SFMOMA: How has the new architecture impacted the Atrium in terms of its role as an exhibiting space?

GG: When the building closed for our recent expansion, a decision was made to remove the Botta stairs, which made a major impact on the new architecture. And now that the Botta stairs are gone and the Snøhetta stairs are there, those two walls come across as an even stronger visual element when you enter the Atrium.

SFMOMA: Neal Benezra, our director, initiated a commissioning program to make the Atrium more of an ongoing part of the museum’s exhibitions. How do the curators go about making decisions about which artists to commission?

GG: All the different curatorial departments were asked to nominate artists. My department, Painting + Sculpture, suggested Julie Mehretu. Julie had recently done a magnificent commission in New York at the Goldman Sachs headquarters. It’s an extraordinary public work of art. And we had already acquired an earlier work by her for the collection, so we had a relationship. We had enormous confidence in her ability to take on a project of this scale. Neal Benezra made the final selection, and we invited Julie to make two new wall murals.

SFMOMA: Before we talk about her project, let’s dwell for a moment on the dynamics of the space as it exists now, after the drastic architectural changes we just discussed. Specifically, how does a viewer’s experience of the space change when it’s activated by artwork?

GG: The Atrium has enormous volume and various strong architectural elements: the oculus, the bridge, the columns. Standing sculpture can be difficult in there because we do so many events in that space and we have to keep the floor open. But artwork can be suspended from the architecture, for instance Matthew Barney’s performance drawing done on the occasion of his retrospective in 2006, Drawing Restraint 14. As well as the big Alexander Calder mobile from the Fisher collection that has been there since the reopening. That piece almost felt like it had been commissioned for that space — the scale was exactly right.

And those walls are such prominent elements architecturally. As big, blank spaces they just call out for something on them. It was a very logical step to think about commissioning an artist to again make paintings for them.

SFMOMA: What has been Mehretu’s process for creating murals to inhabit the space?

GG: Julie’s new works are the largest paintings she’s done on canvas to date, and she spent two years working on them. It’s taken an enormous amount of her time, so her gallery asked that the museum be prepared to acquire the works for the collection, which we were happy to do. Because they’re on canvas, they can be rolled up and go into storage, then come out again in, say, ten years.

SFMOMA: Does she always work at such a significant scale?

GG: Her paintings are often large, but these are some of the largest paintings anywhere in the world. She’s never worked on a canvas this large, let alone two. It’s been an enormous and incredible undertaking.

SFMOMA: Where has she been painting these immense canvases?

GG: In a former church in Harlem, New York. They filled up the entire main floor.

Julie Mehretu at work; courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery; © Julie Mehretu; photo: Tom Powel Imaging, Inc.

SFMOMA: Did she give you a proposal or outline of what she wanted to do?

GG: No, we gave her carte blanche. We’ve been following her work for a long time, and we had total confidence that she would do something exceptional. Her first step was to come out and look carefully at the space. Then she began to dig into the history and identity of San Francisco and the Bay Area. All of her work is involved with history, architecture, cities, social movements, social upheavals, simultaneities and overlays of histories in particular places, how cultures transform — either violently and suddenly, or peaceably over time.

SFMOMA: Like San Francisco after the gold rush, when a few little fishing villages transformed overnight into a city and all kinds of people began to flock to California.

GG: Yes. San Francisco has always been a place known for its openness, its freewheeling cultural values. And it’s always been a city interested in culture and the arts. Julie found herself investigating so many things — the last half century of social protests here, how California was the last piece of the Manifest Destiny puzzle, the displacement of native cultures, first by the Spanish and then by easterners heading west. And all of the myths and ideals that underpinned local history, or drove it, or emerged later to explain it. And of course the more recent technology and social information revolutions.

Julie Mehretu at work at SFMOMA; © Julie Mehretu; photo: Katherine Du Tiel

SFMOMA: Let’s talk about the implications of having an African American woman artist making these enormous depictions of a city like San Francisco that is, at this moment, undergoing such a dramatic transformation, including unfortunately the displacement of people of color by gentrification and the housing crisis.

GG: Julie was born in Ethiopia, but grew up in Michigan — the experience of cultural transformation, migrations, and displacements is part of her own personal history. And that’s something at the heart of the struggle of transition in San Francisco, and at the heart of Mehretu’s work.

The Bay Area has been defined by different waves of immigrants: first the Spanish and then European, Italian, and Irish neighborhoods, and then of course in the nineteenth century the building of the railroads and the enormous numbers of Chinese workers who came here and developed communities. So the city is a constantly changing place. You can’t predict what it will become with any certainty at all. I think when we see the two paintings installed, we’ll witness this incredible movement and transformation — what Julie calls a sense of becoming. She’s interested in things that are on the verge — this city of the twentieth century being displaced by a city of the twenty-first century.