The September 8, 2016, opening of Desirée Holman’s Sophont in Action sparked a question: Can we imagine an anti-racist future? Little did we know that exactly two months later this question would become entirely enmeshed with the enormous weight of the United States presidential election result. An enormous weight not because the election marked a step backward, but rather because it marked what the historian Ibram X. Kendi calls “the progression of racism.” If there has been progress in the challenging of racial inequalities, there has simultaneously been racist progress into new forms, new modes of thought, and new and far-reaching policies that structure the future of education, housing, finance, the law. Racism is not a “backward” idea, an attempt to return to past forms of inequality. It is forward-looking, laying claim to our capacity to imagine the future.

Desirée Holman, Sophont (still), 2015; photo: Charles Villyard

This is why imagining an anti-racist future is so challenging. It does not just entail imagining the eradication of past forms of racism. Nor does it mean imagining a colorblind world. Indeed, in the still-reigning common sense of liberal multiculturalism, replete with its diversity initiatives and sensitivity training, populating a world with a diverse set of actors and even challenging assumptions of white privilege is enough. Popular films and visual culture are filled with images of multiracial futures in which race seemingly does not matter or racism has been recognized as a fallacy. But all too often this visual culture — the places where we often go to learn how to imagine the future — recode the appearance of diversity within new logics of racial discrimination. Imagining a multiracial future is not the same as imagining an antiracist future. The latter requires challenging the progress of racism as it proliferates and transforms our very capacity to imagine the future.

That is why the science fictional, speculative, and fantastical imaginations of world building in the work of Desirée Holman, Naomi Rincón Gallardo, and Jacolby Satterwhite are so vital now and going forward. World building involves creating not just scenarios, but the background rules and landscapes that make possible certain existences and not others. Think of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, or, better, the dystopian world of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993), which now provides such a canny reflection of our own times. It is the science-fictional imagination that provides the powerful context for these performances-in-progress.

Naomi Rincón Gallardo, The Formaldehyde Trip, 2016 (still); photo: Fabiola Torres Alzaga

The tradition of literary speculation is a mixed bag to be sure, ranging from pretending that racism is not a problem, to imagining futures populated only by white people, to reimagining imperial and colonial violence at ever greater scales. While these imagined futures often carry the promise of engaging with problems of racial difference in the form of imagining other species, aliens, et cetera, they all too often reproduce our own world’s deep rifts of racialized economic inequality. But the speculative futures of Butler, Nalo Hopkinson, Samuel Delany, Larissa Lai, Nnedi Okorafor, Ken Liu, Jewelle Gomez, and other emerging writers challenge the usual ways of confronting difference and structures of inequality. In her Xenogenesis trilogy, for example, Butler’s main character is forced to procreate with an alien species and must grapple with the imagination of a future very different from the possibilities that she previously envisioned.

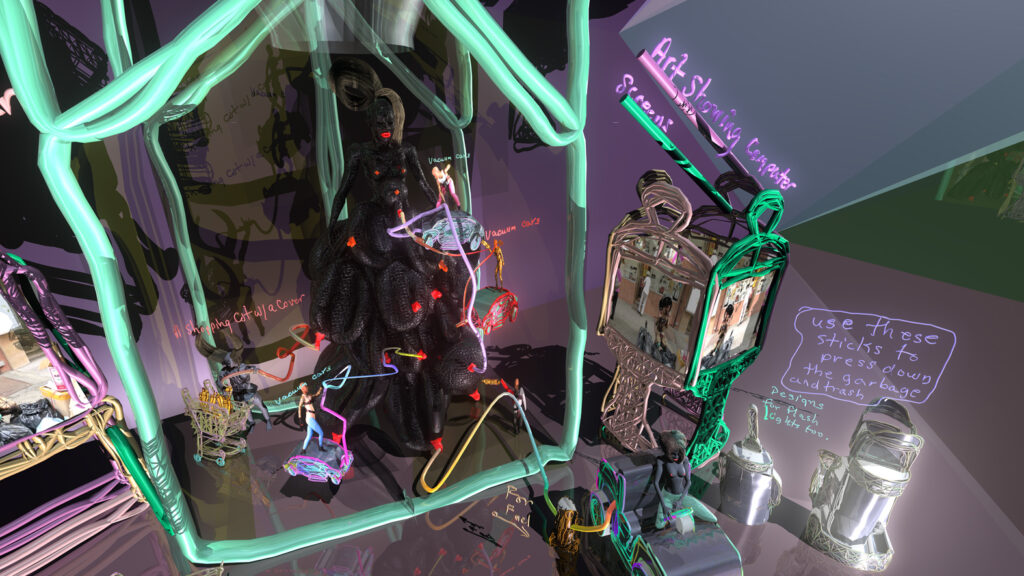

Jacolby Satterwhite, Reifying Desire 6 (still), 2014.

In the hands of Holman, Gallardo, and Satterwhite, world building is a technique to inhabit spaces and times differently and to interrupt the ways in which we inhabit our own world. All three artists exploit the anachronistic and the incongruous — putting together what otherwise might belong in different times and spaces — in order to perform this imagination and interruption. If our usual routines are already saturated by the prospective visions of what could or might happen along racist lines, then their work invites us to enter divergent spaces in the hope of creating other possibilities of world building.