For five decades, seminal photographer Walker Evans documented the language of everyday American life — its hand-lettered roadside signs, its Main Streets and dime-store postcards, its meticulously arranged shop windows. Evans’s inimitable images responded to and reflected the spirit, suffering, and fortitude of a nation, and defined a photographic style that continues to influence artists today. In the following interview, Senior Curator of Photography Clément Chéroux shares his perspective on Walker Evans, an upcoming exhibition that reveals Evans’s uncanny understanding of twentieth-century America.

“Evans felt there was beauty and dignity in those roadside stands and shop windows, in those farmers and workers.”

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham/Roadside Store Between Tuscaloosa and Greensboro, Alabama, 1936; collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: Why Walker Evans? Why now?

Clément Chéroux: History is not frozen. We always need to come back to such important photographers as Walker Evans. Usually big museum retrospectives are organized around the institution’s own collections. This show is a bit different in that it is organized around loans from all the major Evans collections, including the Met, MoMA, the Getty, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery in Washington, the Musée des Beaux Arts of Canada in Ottawa, and a few private collectors, including some very important San Francisco collectors.

SFMOMA: What’s the significance of this show being comprised mainly of loans?

CC: It means that we have the very best prints from the best collections. Working mainly with loans also gave me much more flexibility in the choice of what to include. Another important thing is that most other significant Evans retrospectives have been presented chronologically, from Evans’s modernist beginnings in the late 1920s, the FSA photographs, the Fortune portfolios, and so on, to the last Polaroids he made in the 1970s. What we are presenting in San Francisco is a thematic approach. The theme of the exhibition is Evans’s relationship to the American vernacular.

SFMOMA: How are you defining the American vernacular?

CC: The vernacular, if you compare it to high art, is always low. In American culture, you always speak in terms of high and low. The vernacular is definitely low. It’s common, it’s everyday life, it’s pop culture.

SFMOMA: What was Evans’s relationship to the vernacular, in terms of everyday visual culture?

CC: Evans was always fascinated with American vernacular culture. For example, he collected postcards. Over his lifetime, he collected ten thousand postcards, so that was a real passion for him. He also collected graphic ephemera— at the end of his life every time he saw a bus ticket or a subway ticket on the floor, he would grab it. He was fascinated with everything related to typography, including roadside signs, advertising posters, and things like that. His photography can be explained in part through his fascination with the vernacular as a subject, and that is the first part of the exhibition — all the vernacular subjects he was interested in. Signs, facades, shop windows, and also people, the humble people of his time. The second part of the exhibition examines his interest in the vernacular as a style or as a method. He was deeply interested in vernacular photography.

SFMOMA: You’ve said that vernacular photography is the exact opposite of art — anything that’s not high art.

CC: Exactly. Architectural photography and advertising are both examples. When Evans was making photographs, he was always trying to do it as if he was a vernacular photographer. Meaning, when he photographed American churches, he was photographing them as if he was an architectural photographer. When photographing small-town Main Streets, he was taking the photograph from the same vantage point as a postcard photographer. When he was taking photographs of tools, he did it as if he was photographing them for a catalogue or manufacturer.

Lenoir Book Co., Main Street, Showing Confederate Monument, Lenoir, North Carolina, 1900–40; collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: Why try to replicate that style?

CC: Because at the beginning of his career, he had been visiting Alfred Stieglitz, and in Stieglitz he found a kind of counterexample. Evans was not at all interested in being arty. He thought if you try to push the art in your photograph, it is not going to be interesting. On the contrary, if you try to hide the art in your photograph, that’s going to be very interesting. He was always talking about what he called ‘documentary style.’ He said, “Okay, a police photograph is a document. What I’m doing is not a police photograph, but I’m using the style of the police photographer.” He’s mimicking a police photograph, or an architectural photograph, or an amateur photograph. The heart of his work is in this mimicry. He is not playing the artist, he’s playing the vernacular photographer. And this is what is quite difficult to understand, of course, because he was doing that as an artist.

It’s like a poet who isn’t interested in the classical way of writing poems, but who says, “I heard something that someone said in the street, and it was so poetic, I want to replicate that.” Evans was doing the same thing. He was interested in what was coming from humble people, not the elite. It’s quite similar to what his collaborator James Agee was doing. Agee was very interested in the Bible, for example, and trying to replicate the way of writing in the Bible, or hearing conversations in the street and trying to replicate that. Evans was trying to do that with photography.

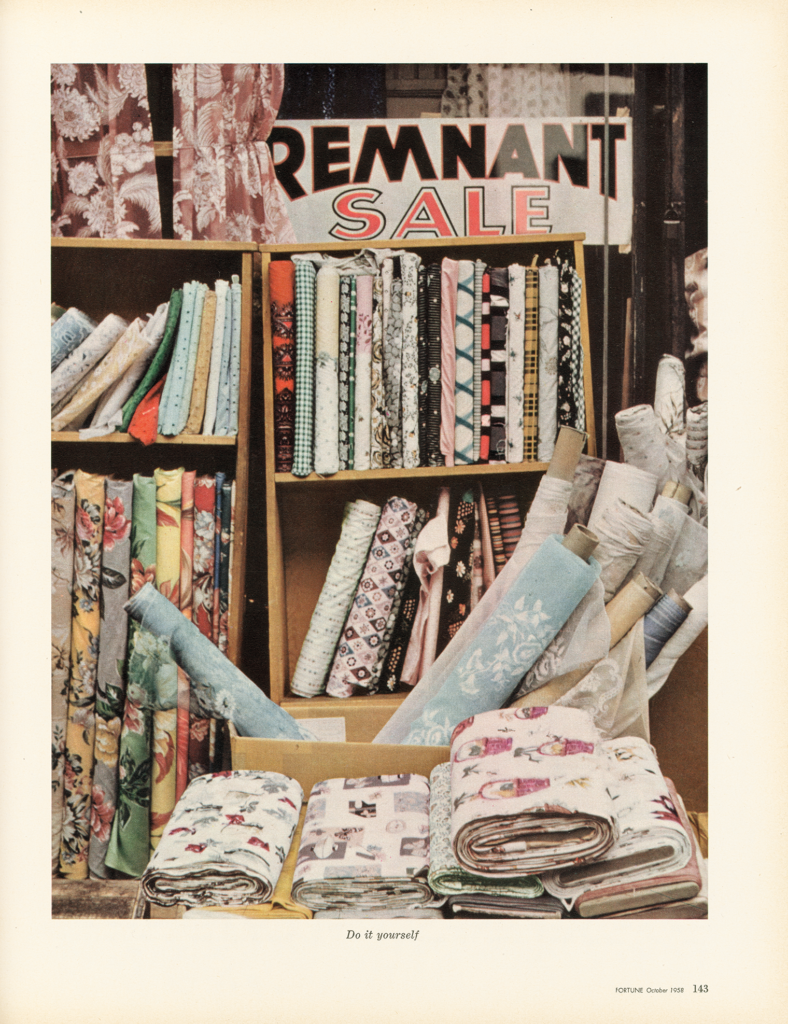

Walker Evans, “The Pitch Direct. The Sidewalk Is the Last Stand of Unsophisticated Display,” Fortune 58, no. 4, October 1958; Centre Pompidou, Musée d’art moderne, Paris, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Collection of David Campany; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: Was Evans’s motivation political, or was it purely aesthetic? Was he creating these photographs as historical documents? Or was it a mix of all of those things?

CC: I would say it was more aesthetic than political. At first I was convinced that he was a leftist. Most of his friends were leftist, like Agee; a few of his friends were linked to the Communist Party, but he was not interested in politics. It’s much more about the aesthetics. But I would say, even more than that, his work is conceptual. He was a conceptual artist before the time of Conceptual art, before the 1960s. He was a conceptual artist since the ’30s. Many historians and curators, such as Jeff Rosenheim and Douglas Eklund at the Met, and also many artists, view Evans as a pre-Conceptual artist. I think we are proving this clearly through our exhibition.

SFMOMA: How was Evans a pre-Conceptual artist?

CC: This is something quite difficult, that he was mimicking vernacular photography — the opposite of what is considered to be art — but at the same time doing that as an artist. It’s a kind of paradox, a kind of dialectical position that’s quite difficult to explain. I think the way that we are trying to explain it is through what we call the “black box” in the exhibition. In that space, we will have some examples of Evans’s collected vernacular photography. When the public sees that, and then looks at his photographs, they will, I hope, understand the relationship between vernacular photography and Evans’s art.

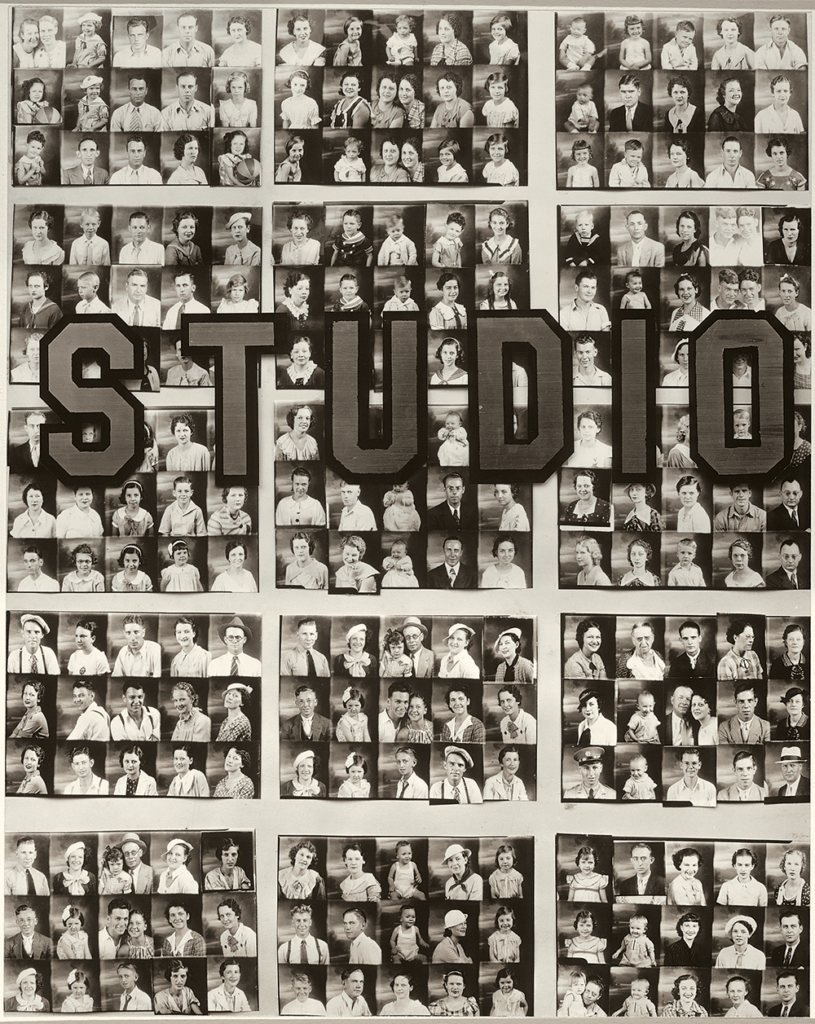

Walker Evans, Penny Picture Display, Savannah, 1936; Pilara Foundation Collection; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: As a curator from outside the U.S., what’s your perspective on the American vernacular?

CC: When you’re from abroad, you are able to see things that people are usually not able to see or to understand, because they are submerged in it. Using that example, I think that I’m better able to see the American vernacular than you, because you are totally submerged in it. The fact that this Evans exhibition will be the first to focus on the vernacular is probably because it is presented by a French curator. For me, it’s extraordinary; for you, it’s probably quite difficult to see.

SFMOMA: Would you say that Walker Evans was able to see it while he was submerged in it?

CC: That’s exactly right. For example, when I wander around San Francisco, I’m able to see how a shop window or sign is painted in a way that’s totally differently than in Europe. There is a specificity to American culture in the way the signs are painted, the way the words are associated. I’m able to see it because I’m not American. Maybe Evans was able to do that because he traveled to Europe for a year before starting his career as a photographer.

SFMOMA: Today’s American vernacular is pretty ugly — I’m thinking of our landscapes of strip malls. But who knows what we’ll all think a hundred years from now.

CC: There are artists today working with the current American vernacular — the typography, the billboards, their colors and surfaces. I agree with you, it’s ugly, but some people are able to see something interesting in that. You asked earlier, did Evans see the American landscape as beautiful? I don’t think it is a question of beauty or ugliness. Evans was interested in it not because he thought it was beautiful, but because he saw a certain aesthetic in it, and that aesthetic says something about America, about the connection between the Industrial Age and democracy.

SFMOMA: It’s interesting that Evans wasn’t of the America that he photographed, but his images don’t feel condescending at all.

CC: No, because he felt there was beauty and dignity in those roadside stands and shop windows, in those farmers and workers. He wanted to share that with the rest of the world by photographing them. And he was very respectful of the people he photographed.

Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1938–41; collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: Which aspects of this show are you most excited about?

CC: I’m very excited about the structure of the exhibition, which is quite new. In all the exhibitions I have curated, there are always different levels of understanding. For some people, it’s going to be about the beauty and the impact of the images themselves. I hope that for some other people, the inclusion of Evans’s photographs and ephemera from his personal collections will allow them to understand his real passion for the vernacular.

SFMOMA: Are you hoping they’ll be able to see what Evans saw in the vernacular?

CC: I hope this exhibition will be able to explain that Evans was one of those artists who could look at the surface of a wall, or at the way a merchant organized his shop window, and find poetry in that. He was able to say, “Look at the world; there is a certain kind of poetry where we don’t normally think we can find it. Open your eyes and look.”