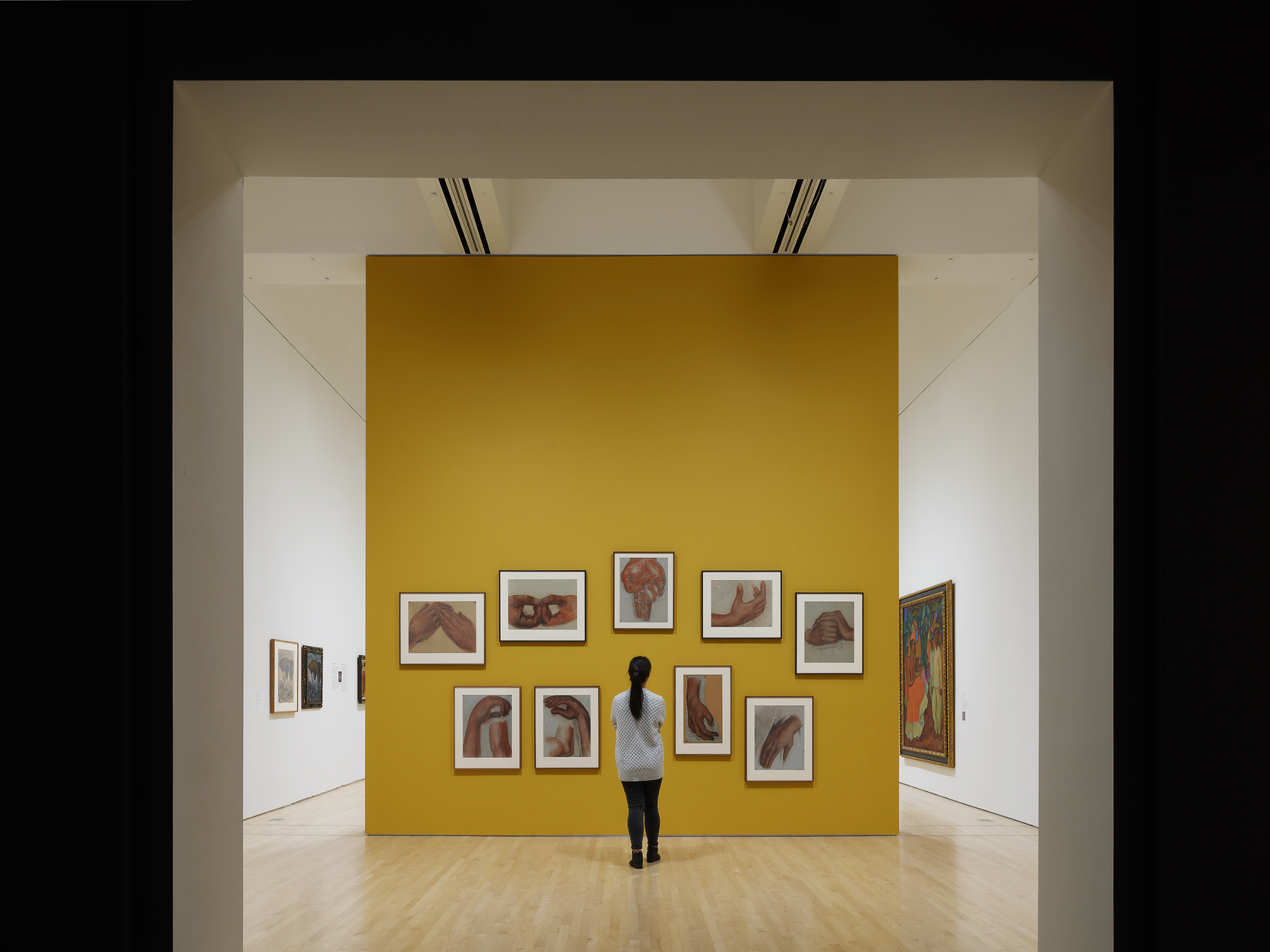

Diego Rivera’s America, (installation view, 2022); photo: Matthew Millman

Experience His America

Diego Rivera’s America, on view through January 2, 2023, revisits one of the most aesthetically, socially, and politically ambitious artists of the twentieth century. The exhibition opens with Rivera’s return to Mexico in 1921, then covers his rise to international fame for social realist paintings focused on Mexican traditional culture and the working class, his trips to San Francisco in 1930–31 and 1940, and concludes with works done at the beginning of the Cold War.

Organized thematically, the exhibition includes galleries dedicated to places like Tehuantepec and Manhattan that captured his imagination, and to his favorite subjects, such as street markets, popular celebrations, and images of labor and industry. In this interview, guest curator James Oles shares insights into Rivera’s bold vision, and themes and works on view. “In each gallery you’ll be surrounded by related paintings and drawings that are like mini-exhibitions that show Rivera’s mind at work,” Oles says.

Diego Rivera’s America is on view July 16, 2022–January 2, 2023. This interview is adapted from a version that appears in SFMOMA’s fall 2022 member magazine.

SFMOMA: So, why this exhibition now?

James Oles: First, there’s been no comprehensive exhibition, worldwide, featuring Diego Rivera in over twenty years. There have been shows on his work in New York City and Detroit in the 1930s. That leaves San Francisco, where he has the most surviving murals, as a key place for an exhibition — although ours is about more than just his experience and impact in the Bay Area.

A presentation of this scale also provides an opportunity for new scholarship on the artist: to find paintings and drawings that have never been shown, and that will be new even to specialists.

At a time when we are so focused on the relationship between art and politics, Rivera reminds us that art matters. For him, it was a weapon in the struggle for a more equitable society. Though he sometimes painted portraits of the rich and powerful, he wanted to shift attention from elite subjects and towards the working class, which in Mexico was often mestizo, if not Indigenous.

SFMOMA: How did Rivera’s life in Mexico and European travels influence his art?

JO: Rivera came from a middle-class background; his parents were teachers. He was born in Guanajuato, a small city north of Mexico City, and in childhood moved with his family to the capital. At age twelve, he entered Mexico’s fine arts school, The Academy of San Carlos, and soon became its most promising student.

While in Paris in the 1910s, French xenophobia heightened his awareness of being outside the European mainstream. When he returned to Mexico in 1921, after the Mexican Revolution, the country was very different politically and artistically. He started exploring Mexican rural traditions and joined the Communist Party, looking anew at people in the working class and embracing them as a subject of art.

Despite years as a leading member of the avant-garde, Rivera ultimately rejected art for art’s sake. His paintings are intentionally constructed to persuade us of the nobility of the working class.

Through Cubism, he also learned that you don’t have to follow the old rules anymore. That’s what modernists do — break the rules, like traditional perspective. His realist style can seduce us into thinking he’s old-fashioned, but he’s not. He’s really a deeply modern artist in that way.

SFMOMA: How is the exhibition structured?

JO: We approach his work thematically. In each gallery, you’ll be surrounded by related paintings and drawings that are like mini exhibitions that show Rivera’s mind at work.

Traditional Mexican life is a major theme of the exhibition’s first half. In 1922, Rivera traveled to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Oaxaca. The local culture, ceremonies, and dress symbolized for many Mexicans the truest roots of their country. This trip was akin to Gauguin going to Tahiti, Matisse going to the south of France, or, later, O’Keeffe going to New Mexico. Rivera was seeking authenticity and connection to an ideal past, far from the modern industrial city. A perfect example of this is Dance in Tehuantepec (1928), one of Rivera’s largest, most radiantly beautiful paintings.

We also dedicate a gallery to paintings of families and children. Rivera painted many images of mothers with children, but why? For him, these were modern-day Madonnas: they might seem apolitical but they are rather charged paintings because for Rivera, these children, nurtured by their perfect mothers, were the future leaders of the revolution. The Flower Carrier (1935), one of Rivera’s most famous works in SFMOMA’s collection, will be shown alongside other paintings of market sellers, showing what makes SFMOMA’s painting special, and highlighting Rivera’s wider vision of the open-air market as a place of color and dynamism, but also daily grinding labor.

Diego Rivera, The Flower Carrier, 1935; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender in memory of Caroline Walter; © Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

SFMOMA: What about the rest of the exhibition? Isn’t “America” the major theme?

JO: By Rivera’s “America” we mean the places in the Americas that mattered to him and where he traveled. Rivera was deeply curious about factories and skyscrapers, and there were no bigger factories or taller skyscrapers than in the U.S. He wanted to engage with sites of working class achievement, which is why, in part, he eagerly accepted mural commissions in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York.

Rivera’s presence in San Francisco is another major topic. Local patrons, like architect Timothy Pflueger, wanted to bring the best to the city, and in 1930 Diego Rivera was the most famous muralist in the world. During this stay, he painted murals for the Pacific Stock Exchange Luncheon Club (now the City Club of San Francisco) and the San Francisco Art Institute.

His works also formed part of the foundational gift that Alfred Bender gave to SFMOMA. The museum now has over seventy works by Rivera. We’ve drawn on these riches for the exhibition and dedicate two galleries to the story of Rivera’s San Francisco mural projects.

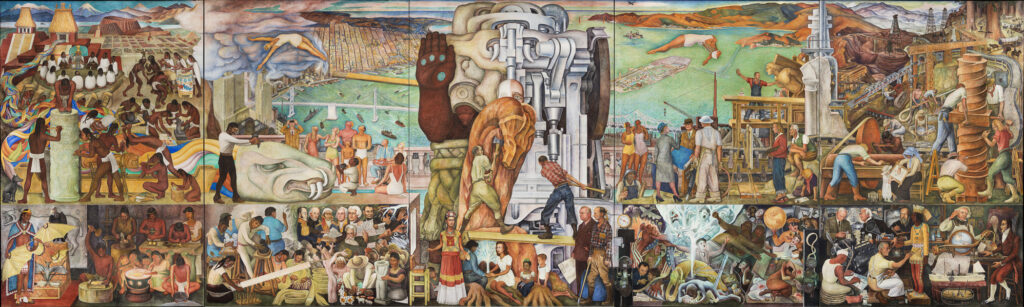

SFMOMA: How does the Pan American Unity mural fit into the exhibition?

JO: Visitors are fortunate to have the monumental 1940 mural on view for free. When it became apparent that a temporary move of the mural from City College of San Francisco was possible, I started to conceptualize the exhibition — one half devoted to Mexico and the other half to the United States — echoing Pan American Unity’s division into a Mexican side and a U.S. side, joined by a panoramic vista of San Francisco.

From the 1920s on, Rivera considered himself an “American” artist in the broader sense of the word, which is used in Latin America to describe the hemisphere, not a single nation. He was challenging Europe’s cultural supremacy but also the rise of totalitarianism there. In 1940, he envisioned the Americas as a place where creativity and innovation would provide a united, progressive front against European fascism.

SFMOMA: What brought Rivera to fresco and murals, and how did you incorporate them in the exhibition?

JO: We open with Rivera’s first mural, Creation (1923). Like most artists of his day, he was not trained in fresco painting. For that first commission, he used a complex, laborious technique called encaustic, which combines pigments with warm wax. Soon thereafter, Rivera and fellow artists started to study fresco because it was associated with what they considered the greatest period in Western art, the Italian Renaissance. They wanted to use that same technique in Mexico to capture the authority, permanence, and dignity of the Renaissance frescoes and secularize them — Mexicanize them — for the post-revolutionary needs of the Mexican government.

They also appreciated how frescoes couldn’t be bought and sold, at least not those in public buildings. By painting in fresco, Rivera believed his murals would be free from the art market, censorship, and destruction.

How to bring immovable murals to life for our audience was a real challenge. We address this by featuring many preparatory drawings and sketches, but also through specially commissioned large-scale film projections of murals in three galleries.

SFMOMA: What are other don’t-miss pieces?

JO: We were lucky to secure the loan of Flower Seller (1926) from the Honolulu Museum of Art. It features one of Rivera’s most important models, Luz Jiménez, an extraordinary Indigenous woman who was herself a skilled weaver and translator, who also appears in paintings coming from Phoenix and Chicago. This is the first time these works will be seen together. We have identified several women who modeled for Rivera, real people he transformed into symbolic types engaged in everyday tasks, like making tortillas or selling flowers in the market. But other figures will always be anonymous.

Diego Rivera, Flower Seller, 1926; Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Philip E. Spalding, 1932; © Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: courtesy Honolulu Museum of Art

We also present the fresco Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees, painted in 1931 for the Atherton residence of Rosalie Meyer Stern and her husband Sigmund Stern, a nephew of Levi Strauss. Rivera painted the mural, now in the collection of U.C. Berkeley, while he and Frida Kahlo were houseguests of the Sterns.

Rivera imagined the mural as a window looking out into the almond grove, where modern farmers work the soil. He added portraits of the Sterns’ grandchildren, Rhoda and Peter Haas, who reach for a bowl of fruit on the window ledge. Their older brother, Walter Haas, Jr., kneels in the background.

In a gallery dedicated to the proletariat, we present two large-scale sketches for Man at the Crossroads, Rivera’s Rockefeller Center mural which was destroyed in 1934, mainly because it included a portrait of Vladimir Lenin. The Communist movement — from Moscow to New York — and proletarian revolution are themes he explored in public murals, but are hard to find in his easel paintings, because most collectors weren’t interested in that aspect of his art.

But with Rivera, things weren’t always serious. We include fun examples of his interest in Surrealism and some over-the-top portraits. In the 1930s and ’40s, Rivera was one of the most in-demand portraitists anywhere. Members of high society would escape to Mexico, particularly during World War II, when it was difficult to travel to Europe. One not to miss is a 1941 double portrait featuring Francis Ford Seymour, who was the wife of Henry Fonda and mother of Jane and Peter Fonda. Seymour appears with her daughter from a prior marriage. This portrait has never been publicly shown until now.

Rivera was also a prolific illustrator of books and magazines, and we’ve selected rare examples that display the political side of his work, particularly his interest in the Mexican Revolution. Additionally, we have a gallery dedicated to his set and costume designs for a 1932 ballet called H.P. (Horsepower), which played for only one night. The original costumes have been lost, so we’re recreating two.

SFMOMA: Last question: Why is Rivera is such an enduring artist?

JO: He is one of the most famous Latin American artists, and many are inspired by his sympathy for the working class, his political activism, and for the way he captures — but also idealized — Mexico. The late San Francisco artist Yolanda López once told me she thought of him as a cultural saboteur. Rivera reminds us that art is not just a form of personal expression, but also a means to transform society — sometimes radically, sometimes just to change sensibilities.

It’s hard to know how much his work changed the world, but for many it changed the question of who was important enough to be represented in art and what art was for. As we emerge from the isolation brought on by a pandemic, Rivera’s images of celebration and labor remind us again and again what we gain through collaboration, and through community.