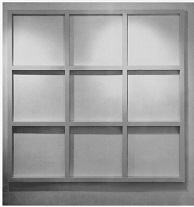

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) recently announced the acquisition of Wall Grid (3 x 3) (1966), an important early work by Sol LeWitt, one of the key artists of the postwar period. Wall Grid (3 x 3) was purchased through the Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions.

Melding form and idea, LeWitt’s works are organized around principles set by the artist establishing procedures, materials, and boundaries that structure the work of art. By subtly shifting his own rules within each work, LeWitt invites viewers to explore the psychology and the flexibility of vision. LeWitt worked in a wide array of materials and mediums but is probably best known for what he called the “wall drawings,” works executed directly on walls at an architectural scale, which he initiated in the fall of 1968 with pencil drawings and later created with crayon, india ink, and acrylic paint. From 1964 to 1968, however, his primary works were three dimensional, executed in wood or steel, which he referred to as “structures,” consciously avoiding the more traditional term “sculpture.” Overall, LeWitt’s work is characterized by precision and clarity of decision making, creating works that range from the intimate to the magisterial, open ended in process but often iconic in result.

In 1964, LeWitt made his first open, modular structures exploring permutations of the grid and the cube, quickly deciding to paint them white so that the work would become more visually integrated with the wall or room. At the same time, he decided to maintain a consistent ratio of 1:8.5 between the material, either wood or metal, and the spaces in between, which he acknowledged was an arbitrary decision, but, once decided upon, was always used. His goal was to capture a structural clarity and simplicity that would allow perception to be revealed at its most fundamental basis; the viewer’s physical movement and active process of perception would be integral to the understanding and experience of the work of art. The work would no longer be a self-contained, self-sufficient object but rather one that would mediate between environment, space, and the viewer’s movement and vision in an attempt to re-engage both classical humanism and the romantic utopianism of the pioneers of abstract art. These works are among the primary achievements of minimalist art. Wall Grid (3 x 3) is a key example of LeWitt’s early structures.

In tandem with the Doris and Donald Fisher Collection, SFMOMA now has one of the largest and most significant collections of LeWitt’s work of any museum or collection in the world. The collection holds a vast selection of wall drawings from throughout his career, including Wall Drawing #1 (1968) to Wall Drawing #1247 (2007), done shortly before the artist’s death. Early handmade structures from 1962 and 1964 are represented, as well a room installation, Incomplete Open Cubes, from the mid-1970s and several examples of the complex cube structures from the 1980s and 1990s. The Fisher Collection includes 24 works by LeWitt, and SFMOMA holds 48 works. Until now, the most significant absent type of work has been one of the minimal structures from the mid-1960s.

SFMOMA’s collection is also exceptional in its representation of key figures and works from the 1960s and 1970s in minimalist art and its context, including not only Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, and Richard Serra, but also painters Brice Marden and Robert Ryman, and precedent figures such as Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin. Also of great importance was the reaction of key artists against minimalist art, including Mel Bochner, Eva Hesse, and Robert Smithson for which LeWitt’s art of the mid-1960s was the touchstone of resistance. LeWitt himself realized he had reached an absolute reductive spareness that he then had to move beyond. Wall Grid (3 x 3) fills a key gap in the collection and will be at the core of any presentation of the museum’s collection of abstract art from the 1960s and 1970s.

The acclaimed SFMOMA-organized exhibition Sol LeWitt: A Retrospective (2000) traced the evolution of LeWitt’s work—including wall drawings, structures, works on paper, photographs, and books—from the austere, reductive aesthetic of the 1960s to the sensual and boldly colored works of more recent years.

About Sol LeWitt

LeWitt was one of the key artists of the 1960s, pioneering both minimal and Conceptual art, movements that abandoned the emphasis on psychological content and gestural form typifying Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. In a seminal text written in 1967 entitled “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” LeWitt emphasized his view of art: “No matter what form it may finally have it must begin with an idea. …When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Conceptualism in art became an internationally influential trend encompassing work by artists with widely different approaches to art making. What linked them was an interest in extending art beyond the boundaries of traditional approaches to painting and sculpture. Using photographs, language, new materials, repeated forms, performance actions, and other methods, Conceptual artists explored new ways of creating artworks that focused on ideas rather than craft. LeWitt was a central figure in the growth of Conceptual art, and his structures and wall drawings remain among its lasting achievements.

Born in 1928 in Hartford, Connecticut, LeWitt moved to New York in 1953, just as Abstract Expressionism was beginning to gain public recognition and was dominating contemporary art. He found various jobs to support himself, first in the design department at Seventeen magazine, doing paste-ups, mechanicals, and photostats, and later for the young architect I. M. Pei as a graphic designer. This contact with Pei proved formative, for as LeWitt would later write, “an architect doesn’t go off with a shovel and dig his foundation and lay every brick. He’s still an artist.”

In 1960 LeWitt took a job at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, working first at the book counter and later as a night receptionist. He met other young artists working there (Dan Flavin, Robert Mangold, Robert Ryman, and Scott Burton), placing him in the midst of a community of young artists searching for a new direction “that would lead away from the pervasive but useless ideas of Abstract Expressionism.” For LeWitt and his colleagues, Abstract Expressionism had become, by the early 1960s, an entrenched style that offered few new creative possibilities for young artists. In contrast to the psychologically loaded brushwork of Abstract Expressionism, LeWitt began to create works that utilized simple and impersonal forms, exploring repetition and variations of a basic form or line as a way to achieve works of a complex and satisfying nature. Perhaps most importantly, he evolved a working method for creating artworks based on simple directions, works that could be executed by others rather than the artist himself.

LeWitt has never forsaken the fundamental approach that he developed in the 1960s, which emphasized ideas over psychological expression and let other people bring these ideas into physical and visual form. Over the years, however, his work has grown more complex in its effects and more complicated in execution. His projects from the 1960s are the most austere and straightforward, while his work from the 1970s inventively compounds the ideas and forms of the prior decade. The early 1980s saw a marked shift to sensual color and surfaces, myriad geometric shapes and their permutations and a more explicitly expressive overall character. In the past five years, the vitality and invention of his work has been especially pronounced, with forms of undulating waves and swirling nets and colors that are often hot and bold.

Wall Grid (3 x 3)

1966

Painted wood

71 x 71 x 1 5/8 in.