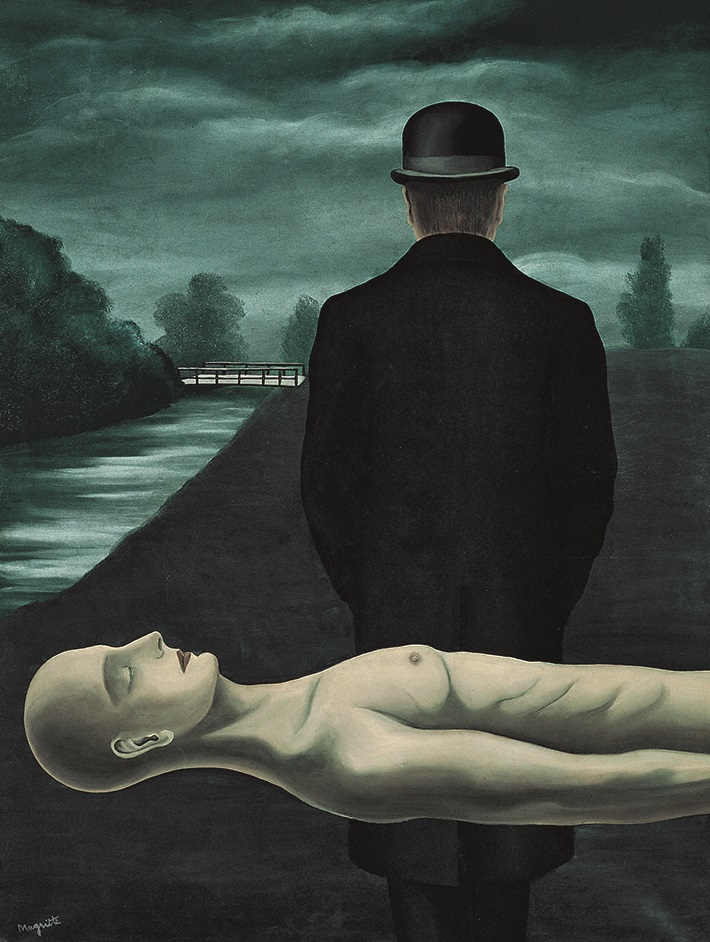

1. René Magritte, Les rêveries du promeneur solitaire (The Musings of a Solitary Wanderer), 1926; Private collection; © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Banque d’Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

The bowler hat, known in French as chapeau melon, is so closely associated with René Magritte that it may come as a surprise to note that the bowler-hatted man did not always appear as an identifiable, regularly recurring motif in his oeuvre. He painted the theme in its classic forms—a single or doubled figure facing forward or backward—no fewer than thirty-six times in oil and seventeen times in gouache between 1926 and 1966. If we include variations such as those seen in Golconde (Golconda) (1955), the tally increases by an additional dozen pictures.1 Yet even though the character originated in Magritte’s early career, all but a few of the paintings with this imagery were made in the 1950s and 1960s. It was only in these final years of the artist’s life that the bowler figure came to be understood as an alter ego and even, at times, a self-portrait.2

The process by which the bowler man passed from anonymous, generic male figure to stand-in for a painter with a distinctly anonymous style is worthy of attention. It deserves consideration not only because Magritte was an artist consumed by the mechanisms and capriciousness of signification, but especially because it helps to reveal how he affected the interpretation of his works after they were done, shifting their public understanding long after the paint was dry and the easel and brushes had been put away.

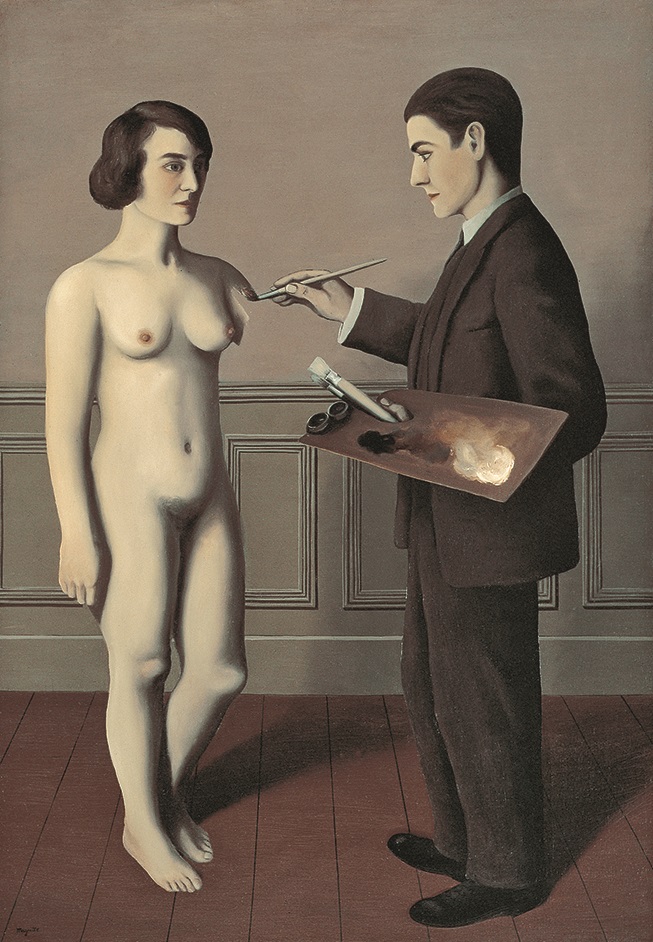

2. René Magritte, Tentative de l’impossible (Attempting the Impossible), 1928; Private collection; © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When Magritte first painted a man in a bowler, in Les rêveries du promeneur solitaire (The Musings of a Solitary Wanderer) (1926, fig. 1), there was no suggestion that the back-turned figure in the black topcoat was in any sense a proxy for the artist.3 Likewise, when two similar types appeared the following year in L’assassin menacé (The Murderer Threatened), this time facing the viewer, there was no reason to think that they might represent Magritte himself. As numerous scholars and critics have pointed out, the ready association for audiences would have been with actors and characters in contemporary films, such as Charlie Chaplin and Fantômas.4 It is equally unexpected that the bowler man would come to be understood as Magritte’s surrogate when considered in light of his confirmed self-portraits. While these are relatively few, in the bestknown examples from his surrealist years, Tentative de l’impossible (Attempting the Impossible) (1928, fig. 2) and La clairvoyance (Clairvoyance) (1936, fig. 3), Magritte resembles the bowler man very little.5 In neither of these pictures does he wear a hat, and in both he holds a palette and brush. Notably, they are constructed around the dramatic moment of applying a stroke of paint, demonstrating that the image of the working artist, however fantastically construed, was key to his self-presentation. By contrast, the most “painterly” action by a bowler man appears in La cinquième saison (The Fifth Season) (1943), where two such figures hold framed pictures under their arms. Despite the potential for a meta-artistic reading of the scene, Magritte’s first published description of it downplays this suggestion by failing to identify the men in any specificity. According to this early discussion of the work, they might be collectors, dealers, or simply porters.6

3. René Magritte, La clairvoyance (Clairvoyance), 1936; private collection; © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Magritte’s long-time dealer Alexander Iolas was likely the first to associate the artist with his bowler men. More than once Iolas described the figure in La boîte de Pandore (Pandora’s Box) (1951) as “your portrait in a Brussels street.”7 He also referred to Le chant des sirènes (The Sirens’ Song) (1952), which includes another backward-facing bowler man, as “your portrait.”8 Prior to these identifications, the type seemed to bear no more than a passing resemblance to Magritte. As many have noted, both the painter and these figures were of “average height and build . . . conservatively dressed in dark clothes, neatly collared and tied,” and, above all, were likely to go “unnoticed in a crowd.”9 While there is no question that Iolas was in regular communication with Magritte and was in a position to know his thoughts about these works, the dealer’s comments stress a specific reading of the pictures that, to this point, the artist had left openended. But Magritte would soon make anonymity a defining feature both of his painted bowler men and of his own public presentation. Moving forward, these “blank” figures—nondescript in precisely a way that would allow for the projection of anyone’s selfhood—would unmistakably become emblems of Magritte.

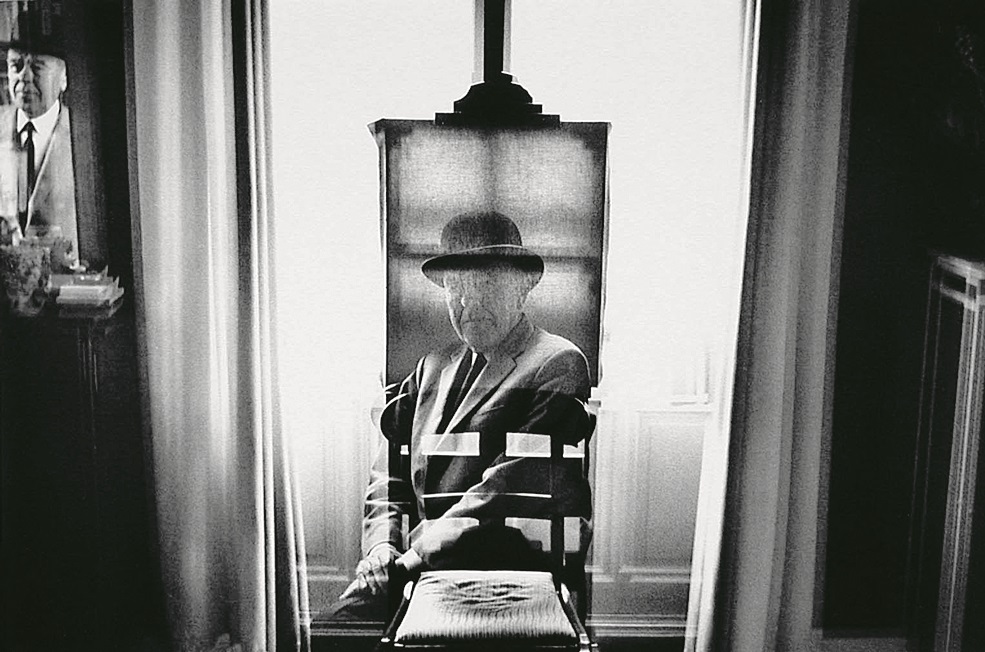

4. Duane Michals, Rene Magritte, 1965; collection SFMOMA; gift of Van Deren Coke; © Duane Michals; photo: Courtesy of the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

The connection between and near assimilation of Magritte and the bowler-hatted man were not merely the result of the figure’s frequent appearance in the artist’s late paintings. Indeed, he worked energetically during the 1960s to ensure this equivalence, particularly when he found himself before the camera (fig. 4).10 In examining how this motif became tied to Magritte’s public persona, it is helpful to consider his shifting thoughts about his professionalism and what it meant to be an artist in the postwar era.

Those who spent time with Magritte have said that he had a “desire to live without history (even his own) and without style . . . to render himself invisible.”11 As the bowler-hat type evolved, the artist developed new ways for it, too, to skirt detection. After becoming regularized in the 1950s, when the broad landscape of La boîte de Pandore was cropped closely to the figure, variations on the theme could be placed along a spectrum of presence and absence. In some instances the form has a robust corporeality and volume; in others, such as La belle société (High Society) (1965–66), it feels entirely flat. Around this time Magritte also explored a hollow silhouette that makes the motif’s propensity for invisibility fully manifest. First in L’ami de l’ordre (The Upholder of the Law) (1964) and later in L’heureux donateur (The Happy Donor) (1966), a bowler man–shaped aperture allows the familiar contours of the figure to assume the dimensions of the canvas, framing a view onto a different scene like a variation of his paintings of pictures within pictures. Among their other traits, these examples literalize the bowler man’s tendency to disappear within a crowd.

Magritte has aptly been described as “The Master of the Bowler Hat.”12 This phrase is an especially happy one because, more than just pointing out a preoccupation of the painter’s late career, it uses the nomenclature of art historical anonymity. If the names of many medieval and Renaissance masters are lost to us due to a lack of archival documentation, Magritte made himself anonymous by playing the bookkeeper, the bourgeois cipher. Here is Magritte himself in 1966: “The bowler . . . poses no surprise. It is a headdress that is not original. The man with the bowler is just middle-class man in his anonymity. And I wear it. I am not eager to singularize myself.”13

Why was anonymity a useful tool for Magritte in his work of the 1950s and 1960s? It offered, I would suggest, an effective means of destabilizing his audience by challenging the typical patterns of engagement for artist and viewer. No one would dispute that originality and subjectivity were central to the tradition of modern painting that Magritte entered into. But by the end of his career, artists one or two generations younger, from Jasper Johns to Vija Celmins, were in search of alternatives to modernism’s most prevalent creative tropes.14 Magritte’s particular refusal to conform to type was productive not only because it offered an affectless model of painting but also because it placed a different set of demands on audiences. By shedding any claim to individuality and thus subjectivity, Magritte declined to present himself as a motivating force behind his images. In the face of this soft “death of the author,” a viewer cannot alleviate the mystery of a confounding picture by tracing it back to a unique maker who supplied its origin. Try to use me as an interpretive key, Magritte seems to say, and you will be led to an empty place, a hollow source.

The curious possibility that a painting of a generic figure might become a portrait after the fact defies any logic of meaning-making in which artistic intention is primary. But it was hardly foreign to Magritte. As early as 1943 he was quoted by his friend and fellow Surrealist Louis Scutenaire: “It can happen that a portrait tries to resemble its model. However, one can hope that this model will try to resemble its portrait.”15 By the 1960s Magritte had facilitated just this sort of reversal—and he achieved something else as well. In the same way the poet Paul Colinet could refer to the imagery of La clairvoyance as “two different forms of the same bird,” Magritte’s self-portraits of the 1920s and bowler-hat figures of the postwar period show two different sides of the same artist.16 Whether posing for the camera or serving as the eponymous patron in L’heureux donateur, Magritte was acutely attuned to what happened with his pictures after the painting was done. He fashioned himself an anonymous artist in the studio, and then, reversing the mirror, he made himself a model of anonymity.

Notes

- For essential aid in research I thank Alex Zivkovic. A complete census of the bowler figures would also include their appearances on painted bottles and in collage, as well as the use of the hat as a sculptural object.

- For more on the bowler-hatted man as Magritte’s alter ego, see Sandra Zalman, “Secret Agency: Magritte at MoMA in the 1960s,” Art Journal 71, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 100–113; Sandra Zalman, “Pipe Dreams: In Search of an Allegorical Magritte,” in Gravity in Art: Essays on Weight and Weightlessness in Painting, Sculpture and Photography, ed. Mary D. Edwards and Elizabeth Bailey (Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland and Company, 2012), 243–52; and Suzi Gablik, “The Bowler-Hatted Man,” in Magritte (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 154–72. Magritte’s 1964 painting Le fils de l’homme (The Son of Man) features a bowler man intended as a self-portrait, while the figure in the 1966 canvas L’heureux donateur (The Happy Donor) reads as such when one learns that Magritte himself donated the work to the Musée d’Ixelles, Brussels.

- While few dispute the anonymity of the figure, art critic and curator David Sylvester suggests that the setting may be a “conscious or unconscious” reference to the landscape near Magritte’s childhood home. David Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 1, Oil Paintings, 1916–1930, by David Sylvester and Sarah Whitfield (Houston: The Menil Foundation and Philip Wilson Publishers, 1992), 198.

- On cinematic references latent in the bowler image, see, for example, Anne Umland, “‘This Is How Marvels Begin’: Brussels, 1926–1927,” in Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938, ed. Anne Umland (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2013), 32–35; and Peter Wollen, “Magritte and the Bowler Hat,” in Paris Manhattan: Writings on Art (London and New York: Verso, 2004), 133–35.

- Five self-portraits have been identified in oil and two in gouache. The oil paintings are Tentative de l’impossible, La clairvoyance, La lampe philosophique (The Philosopher’s Lamp) (1936), Le sorcier (The Magician) (1951), and Le fils de l’homme. The gouaches are La lampe philosophique (The Philosopher’s Lamp) (1936) and La maison de verre (The Glass House) (1939).

- “In a street, a man who carries a picture of the sky under his arm meets a man who carries a picture of the forest under his arm.” René Magritte, Dix tableaux de Magritte, précédés de descriptions (Brussels: Le miroir infidèle, 1946), n.p. My translation.

- Alexander Iolas, quoted in David Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 3, Oil Paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949–1967, by Sarah Whitfield and Michael Raeburn (Houston: The Menil Foundation and Philip Wilson Publishers, 1993), 190.

- Alexander Iolas, quoted in Sylvester, 198. It has been noted that the phrase “your portrait” does not necessarily indicate that Iolas viewed these as self-portraits. Yet, since both figures are turned with their faces out of view, any inclination to describe them as portraits, rather than simply as pictures of men, points to an understanding that each was, in some sense, a painting of a particular individual, and most intuitively Magritte. On La boîte de Pandore: “There is no indication that Magritte regarded it as a self-portrait.” Sylvester, 190.

- Patrick Waldberg, Magritte: Peintures (Paris: L’autre musée/La différence, 1983), 17, quoted in Stephanie Barron, “Enigma: The Problem(s) of René Magritte,” in Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images, ed. Stephanie Barron and Michel Draguet (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2006), 25.

- The work of Duane Michals, who published pictures of the artist including René Magritte (1965, figure 4) in “This Is Not Magritte,” Esquire (February 1966): 100–103, and Steve Shapiro, who published photographs of Magritte wearing a bowler in “The Enigmatic Visions of René Magritte,” Life, April 22, 1966, 113–19, is especially relevant in this regard. Magritte did not typically wear a bowler but developed a “habit of putting on a bowler hat to pose for the camera.” David Sylvester, Magritte, 2nd ed. (Brussels: Mercatorfonds in association with the Menil Foundation, 2009), 15.

- Gablik, “The Bowler-Hatted Man,” 154. Consider as well Magritte’s remark to Gablik: “I don’t want to belong to my own time, or, for that matter, to any other.” René Magritte, “Interview Suzi Gablik” (1967), in René Magritte: Écrits complets, ed. André Blavier (1979; repr., Paris: Flammarion, 2009), 645–46.

- Wollen, “Magritte and the Bowler Hat,” 128.

- René Magritte, quoted in “The Enigmatic Visions of René Magritte,” 117.

- For a discussion of Magritte’s influence on these generations of artists, see Barron and Draguet, Magritte and Contemporary Art.

- René Magritte, quoted by Louis Scutenaire in Magritte (1943), in Harry Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1977), 194.

- Colinet wrote this to describe the second panel of Magritte’s surrealist panorama Le domaine enchanté (The Enchanted Domain) (1953), which incorporates the egg and bird imagery of La clairvoyance. See pages 114–15 in this publication. Note that Magritte did not include a bowler figure in any panel of Le domaine enchanté.

Photo: Andria Lo

Photo: Andria Lo