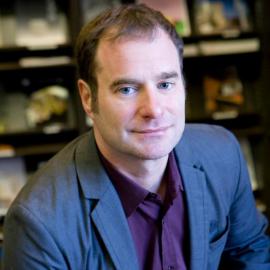

Matson Jones window from “Recreations in dimension of 18th-century still lives,” Tiffany’s, November 9, 1956

The intensity of the creative dialogue between Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in the 1950s has long been recognized by scholars, critics, and curators. Each artist famously influenced and inspired the other during the early, wildly inventive years of their careers in New York. “We gave,” in Rauschenberg’s words, “each other permission.” The issue that poses a more difficult interpretive challenge is the domestic partnership and sexual intimacy the two men shared during this same period, roughly from 1954 until 1961. Until fairly recently, scholars and critics generally followed the discretion shown by the artists themselves who (understandably) preferred not to acknowledge their romantic relationship, or their sexual orientation, in print. Since the early 1990s, however, a number of art historians have argued for the importance of homosexuality for understanding their respective achievements. For instance Jonathan Katz, a pioneering voice in this arena, has interpreted particular iconographic references in Rauschenberg’s Combines—from a picture of Judy Garland in Bantam (1954) to the “evocation of the Ganymede myth” in Canyon (1959)—as allusions to the artist’s identity as a gay man.1

One challenge inherent in this method of interpretation is that it tends to select some details from Rauschenberg’s work while largely ignoring others, including the abstract or partially abstract passages of paint and fragments of wallpaper, wood, cardboard, printed matter, and bric-a-brac that populate the Combines. The precisely composed but densely packed visual traffic of Rauschenberg’s early work resists stable meanings and coherent narratives, and the artist’s sexuality simply cannot be treated as the key that unlocks the interpretive puzzle of his work. There is no secret meaning trapped inside the Combines or silkscreens, or lying just beneath their surface, or covered by veils of illusion that an art historian may simply remove or read through. Those surfaces, forms, and veils are the meaning and matter of the work no less than the recognizable imagery the work contains.

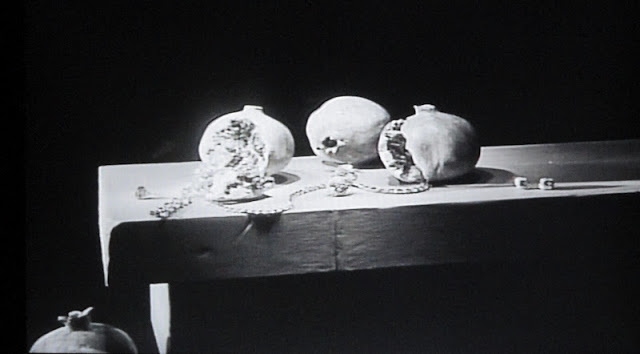

Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper—Studio N.Y.C., 1958, printed 1981; collection SFMOMA; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

In what follows, I propose a different, if admittedly limited, approach to the status of homosexuality within the early careers of Johns and Rauschenberg. As will become clear, that status was marked by distance and concealment rather than affirmation or disclosure.

In the 1950s, Rauschenberg and Johns undertook a number of commercial art projects, including window displays for Fifth Avenue department stores and graphic designs for corporate clients and magazines. They worked under a pseudonym so as to avoid the taint of commerce, which they worried would damage their reputations as avant-garde artists. In a 1955 letter to Rachel Rosenthal, an artist and close friend of the couple, Rauschenberg noted that “our ideas are beginning to meet the insipid needs of the business. . . . Our shame has forced us to assume the name of Matson Jones Custom Display.”2 “Matson” was the maiden name of Rauschenberg’s maternal grandmother, and “Jones” is a phonic near cousin to “Johns.” “Matson Jones” sounded like the name of one man but stood for a collaborative endeavor whose output was both explicitly public (shop windows on Fifth Avenue) and obscurely pseudonymous.3 Although unknown to the public at large, the identity of the couple behind Matson Jones was well known to the artists’ friends and associates, including of course the clients commissioning their work. The secret of their commercial careers was a partial one at best.

Matson Jones was a successful enterprise in financial terms. In recognition of the inventiveness of their designs for the windows of Bonwit Teller and Tiffany’s, the firm was paid top dollar at the time ($500 per project) by display director Gene Moore. In a series of memorable windows, Matson Jones re-created eighteenth-century Spanish still life paintings in three dimensions. Using plaster casts and paint, Rauschenberg and Johns meticulously reconstructed the lemons, pomegranates, oranges, and grapes shown in the original pictures. Each tableau also included replicas of the bowls and tables on which the fruits were displayed in the original paintings. The compositions differed, however, from their historic sources in one crucial respect: they featured diamond and emerald baubles draped around, and in some cases extending from, the fruits. The unexpected juxtaposition of painted pomegranates or lemons and luxury jewelry created an elegant, lightly surrealist effect.

Andy Warhol also designed window displays for Gene Moore in the 1950s. But in contrast to Rauschenberg and Johns, Warhol never saw commercial art as insipid or shameful—indeed, he acknowledged commerce as an essential component of his own (and in fact every artist’s) enterprise. This embrace contributed to the dismissal of his fine art by critics and other commentators. Having met Warhol in the late 1950s, the writer Truman Capote later recalled, “I never had the idea he wanted to be a painter or an artist. I thought he was one of those people who are ‘interested in the arts.’ As far as I knew he was a window decorator. . . . Let’s say a window-decorator type.”4 Capote’s remark conveys his disdain for “window decorator types” who lack the rigor (or talent or seriousness) to become authentic artists. It associates Warhol with a stereotype of the fey decorator whose aesthetic interests run to throw pillows and window treatments rather than vanguard painting and sculpture.

In his 1980 memoir Popism: The Warhol Sixties, Warhol recounts a related conversation with his friend Emile de Antonio (“De”), an agent and filmmaker who was also close to Rauschenberg and Johns. “I’d been wanting to know for a long time,” writes Warhol, “why they [Rauschenberg and Johns] didn’t like me. Every time I saw them, they cut me dead. . . . I finally popped the question and De said, ‘Okay, Andy, if you really want to hear it straight, I’ll lay it out for you. You’re too swish, and that upsets them. . . . You’re a commercial artist, which really bugs them because when they do commercial art—windows and other jobs I find them—they do it just ‘to survive.’ They won’t even use their real names. Whereas you’ve won prizes! You’re famous for it!”5 According to this account, Warhol’s public recognition as a commercial artist reinforced his “swishness” as an effeminate homosexual. Yet, true to character, Warhol affirmed rather than denied this aspect of his identity: “And as for the ‘swish’ thing, I’d always had a lot of fun with that—just watching the expressions on people’s faces. You’d have to have seen the way all the Abstract Expressionist painters carried themselves and the kinds of images they cultivated, to understand how shocked people were to see a painter coming on swish.”6 Warhol contrasted his flamboyance with both the machismo of the Abstract Expressionists (he elsewhere specifies Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning as the painters he has in mind) and the conservatism and closeted sexuality of Rauschenberg and Johns.

Warhol’s anecdote about the disdain of Rauschenberg and Johns toward him is a good one, and there is no reason to doubt its authenticity. It is, however, a story that appeared in print three decades after the fact. I have written elsewhere on how Warhol’s homoerotic drawings of the 1950s led to the dismissal of his art, and how his celebrated Pop art paintings of the 1960s were indirect, at best, in their allusions to same-sex desire.7 However “swish” he may have presented himself to friends and colleagues, Warhol also found ways to negotiate the normative codes of American art at the time.

Rauschenberg and Johns were correct to fear that their commercial work might be used to discredit the work they exhibited in fine art galleries. Writing in Arts magazine in 1959, the critic Hilton Kramer belittled Rauschenberg as “a very deft designer with a sensitive eye for the chic detail, but the range of his sensibility is very small—namely from good taste to ‘bad.’ . . . Frankly, I see no difference between his work and the decorative displays which often grace the windows of Bonwit Teller and Bloomingdale’s. . . . Fundamentally, he shares the window decorator’s aesthetic: to tickle the eye, to arrest attention for a momentary dazzle.”8 Phrases such as “chic detail” and “momentary dazzle” undercut the seriousness and ambition of Rauschenberg’s work while insinuating a stereotypical view of window decoration and effete taste-making. Notice that Kramer does not divulge the fact that Rauschenberg created “decorative displays” for Bonwit Teller; he simply uses that knowledge to demean the artist and signal to those in the know, including Rauschenberg himself, the perils of being associated with window dressing.

In the final sentence of the review, Kramer’s rhetoric is inflated to such a degree that it sounds, in retrospect, nearly parodic. In reference to both Rauschenberg and Johns, he writes, “Like Narcissus at the Pool, they see only the gutter and are exhilarated to think art can be proliferated out of a milieu in which they feel so comfortably at home.”9 For Kramer, window display was a place of utter degradation and deviant self-regard. The professional practice of art criticism in the 1950s did not allow for any affirmative discussion of same-sex desire and experience. When it appeared within that discourse, homosexuality was lodged within the registers of connotation and double entendre (“Narcissus at the Pool”), of indirection and insider knowledge (“the windows of Bonwit Teller”). This means that the experience of homosexuality in the 1950s, whether Rauschenberg’s, Warhol’s, or anyone else’s, cannot be understood within the coherent, confident terms of what we now call gay identity.

The question of sexual minorities within the history of art is not limited to the erotic lives of artists or visual representations of alternative desires. It is also a history of critical and popular knowledge, of when and under what conditions homosexuality is “speakable” in relation to particular artists. In the case of Rauschenberg and Johns, that speakability was all but impossible in the 1950s, a decade that Katz has rightly described as the most homophobic in the twentieth century. The Stonewall Riots of 1969, in which the patrons of a Greenwich Village gay bar resisted arrest and sparked two days of protest, are generally seen as the birth of the modern gay liberation movement. The 1970s ushered in a period of greater public visibility—if not always acceptance—of homosexuality. Both Warhol and, to a more limited degree, Rauschenberg were able to acknowledge their sexual identities more openly in the decades after Stonewall than would have been imaginable before.

A remarkable conversation between Rauschenberg and the Australian critic Paul Taylor appeared in 1990 in Interview magazine, published by Andy Warhol Enterprises. Taylor, a gay critic who died as a result of AIDS a few years after the interview, was well known for his commitment to postmodern art, especially work addressing questions of gender and sexuality. At the time the interview took place, the country was in the midst of a “culture war” over homosexuality and federal funding to the arts, as manifested most notoriously in the cancellation by the Corcoran Gallery of Art of a full-scale retrospective of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe under political pressure from the right, and the subsequent trial of another museum and its director on obscenity charges for mounting the same show.10 Taylor reminds Rauschenberg of this context as he opens the delicate subject of the artist’s relationship with Johns:

PT: We have previously talked about your relationship with Jasper. How much will you go on the record about this? I think there are lots of reasons to talk, especially in the current climate of suppression of gay art and artists.

RR: Well, I wouldn’t go into any kind of sexuality. One of the reasons is that—is this off the record?11

Given this exchange, one might expect the topic of sexuality to be positioned beyond the bounds of public knowledge (“off the record”). Instead, something quite different happens:

PT: Can’t you say it in a way that’s on the record?

RR: Well, I think I’d better just leave it alone. I’m not frightened of the affection that Jasper and I had, both personally and as working artists. I don’t see any sin or conflict in those days when each of us was the most important person in each other’s lives.12

After decades of silence on the subject, Rauschenberg acknowledges his intimacy with Johns in a manner all the more moving for its indirectness and slightly awkward wording. Terms such as “gay,” “lover,” “boyfriend,” or “homosexual” are never uttered. Instead, Rauschenberg describes his relationship to Johns as one of both personal and artistic “affection,” and recalls the moment when “each of us was the most important person in each other’s lives.” At this moment in the interview, Rauschenberg describes the supreme importance of Johns as both his romantic and professional partner and affirms the reciprocity of that feeling in their relationship. Even as this recollection avoids explicit reference to sexual intimacy or identity, it makes quite clear the multiple forms of affection the two men shared in the 1950s.

Toward the end of their exchange, Taylor asks Rauschenberg why he and Johns broke up. Surprisingly, Rauschenberg ascribes the reason for the split not to any interpersonal conflict but rather to the wider social world of which they were part:

PT: Can you tell me why you parted ways?

RR: Embarrassment about being well known.

PT: Embarrassment about being famous?

RR: Socially. What had been tender and sensitive became gossip. It was sort of new to the art world that the two most well-known, up and coming studs were affectionately involved.13

Rauschenberg blames “gossip” and “embarrassment” for the break with Johns, meaning that they were uncomfortable with the attention their relationship aroused among others in their social and professional orbit. Whether the “gossip” stemmed from envy (as, perhaps, in Warhol’s case) or disapproval (as, for example, in Kramer’s review) is not specified. The last sentence of the exchange is particularly telling in its combination of machismo (“up and coming studs”) and tenderness (“affectionately involved”).

The intimacies that Rauschenberg and Johns shared are of rightful interest to art history insofar as their creative and affectionate “involvement” was a decisive influence on their art of the 1950s. There is no way to fully comprehend how Rauschenberg and Johns “gave each other permission” as visual artists without acknowledging their relationship as sexual and domestic partners at a moment when such partnerships were all but unspeakable in American society. In another sense, however, the intimacy between the two is theirs alone. No one else can claim to know the contours of their affection at the moment when they were “the most important person in each other’s lives.” What we can do is recognize and admire what was clearly the enormously generative power of their love.

Notes

- Jonathan Katz, “The Art of Code,” in Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership, ed. Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), reprinted at https://www.queer-arts.org/archive/show4/forum/katz/katz_set.html.

- Rauschenberg, letter to Rachel Rosenthal, quoted in Kirk Varnedoe, Jasper Johns: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 125.

- As Gene Moore recalled, “They didn’t want their commercial work to be confused with what they considered their real art.” Gene Moore and Jay Hyams, My Life at Tiffany’s (New York: St. Martin’s, 1990): 70.

- Quoted in Victor Bockris, The Life and Death of Andy Warhol (New York: Bantam, 1989), 89–90.

- Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, Popism: The Warhol Sixties (New York: Harcourt, 1980), 11.

- Ibid., 12.

- Richard Meyer, Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002): 94–157.

- Hilton Kramer, “Month in Review,” Arts 33, no. 5 (February 1959): 49.

- Ibid.

- On the Mapplethorpe controversy, see Meyer, Outlaw Representation, 2–5, 206–23.

- Paul Taylor, “Robert Rauschenberg: I Can’t Afford My Own Work,” Interview 20, no. 12 (December 1990): 147.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.