Photographs teach us the “certainty” of extrinsic reality; at the same time they teach us the “uncertainty” of what happens when reality is internalized in our thought process. When we look at photographs merely as information, there are no evident changes in our impressions of them over time. But our mental state continually changes on a daily basis. It stands to reason that the meaning given by a photograph will change depending on the change in the mental state of the person viewing the photograph. That may occur after my talk tonight. I hope that it is not a “meaningless change” but a “good change.”

I looked at the PhotoAlliance website before I came. There was an announcement about my talk, and I was struck by the phrase “our relation to changes in the natural and man-made landscape we inhabit.” Here, also, is the word change. There is also the word landscape. And the word natural as well as the word man-made. Finally the word inhabit. I thought these five words aptly expressed my interests.

As we see my photographs tonight, I think we will be thinking about these words. If I were to add another important word, it would, of course, be photography. Change, nature, man-made, landscape, inhabit: how do these words intersect with our topic of interest, photography?

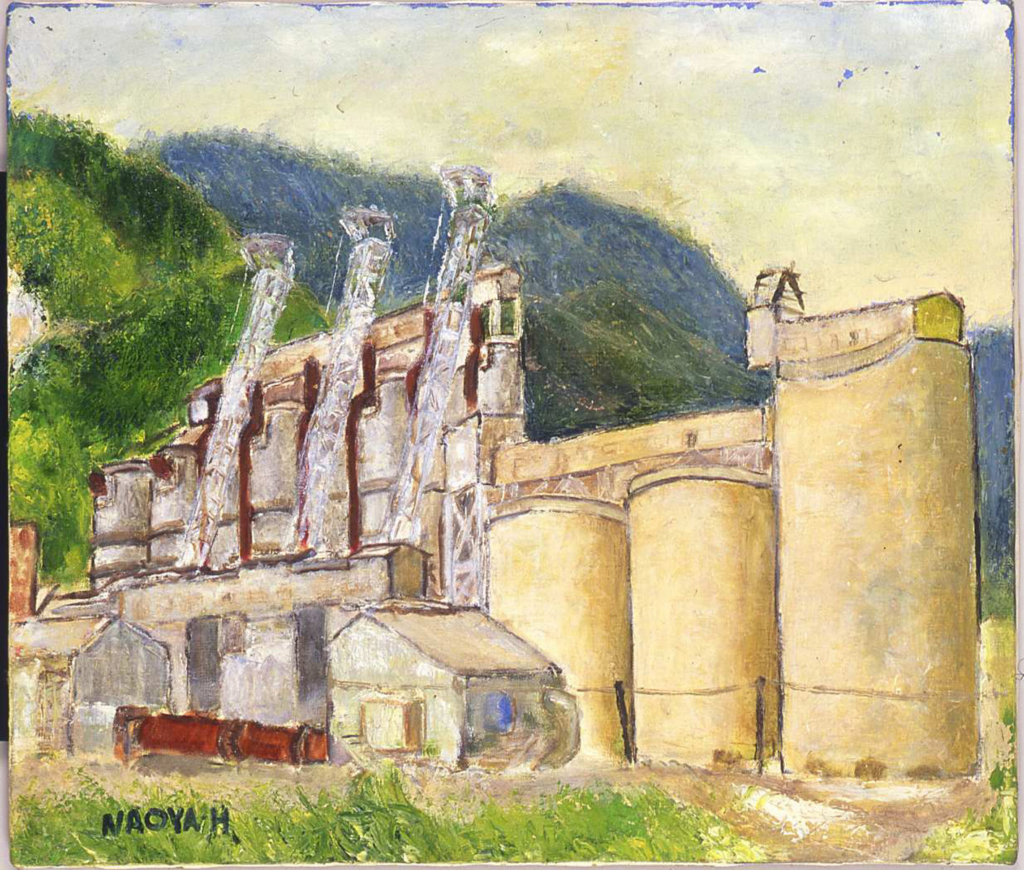

This clumsy oil painting is one I made when I was seventeen years old (fig. 1). For reasons that I don’t know, my interest in art increased dramatically when I was in high school. I was born in Iwate Prefecture, in the northern part of Honshu, the largest of Japan’s four major islands. In English Iwate means rock and hand, an unusual place name. They say that this place name is from a legend in which an ogre promised the gods, “I won’t behave badly anymore,” and pressed his handprint into a rock. I don’t know if it was due to this place name, but from childhood I liked hard things better than soft. I preferred rocks and metals to animals and plants. It was the cement factory that I passed by every day on my way to high school that I chose as my subject for the first oil painting I made on canvas.

1. Naoya Hatakeyama, student painting, 1975; © Naoya Hatakeyama

In 1979 I entered the art department of the University of Tsukuba, some sixty kilometers north of Tokyo. There I met Kiyoji Otsuji, a remarkable professor, and became interested in photography. If I start talking about my student days and about Professor Otsuji, I will run out of time, so I will switch to what happened after I finished university and began to live in Tokyo.

Before that, though, I will say that while I was studying photography in school, the influence of American photography on Japan was enormous. I still recall that in his first lecture, Professor Otsuji introduced us students to the work of Lee Friedlander. At that time in Japan the active developments in photographic expression that took place in America in the 1970s, such as documentary photography, new landscape photography, new color photography, and new criticism, were being transmitted, providing stimulation to the many young people studying photography.

In particular what influenced the young generation in Japan was the stance of several American photographers who confidently shot photographs of their everyday lives and landscapes where nothing special was occurring. It wasn’t necessary to go off to a special place or meet a special person in order to take photographs. All it took was to click the shutter, aiming at what was right in front of one’s eyes at the moment. It appeared as if those photographs were telling us that. Those photographs taught us the magic of how ordinary scenes in the real world become something special by having been photographed. Vast numbers of “ordinary” photographs were taken mostly by the young generation. The older generation called this “con-pora photography,” shortening the word contemporary, and looked dubiously upon this movement.

My work may be a flower that blooms from the pollen of the large, beautiful flower that bloomed in America in the seventies, which was transported by the wind across the Pacific Ocean and pollinated another flower from a far-off western island, resulting in the seed of a new plant. The question is whether that flower is appealing. This is what I hope you will observe.

As you know, Tokyo is one of the world’s most dense cities. When I began to live in the city after finishing college, I came across a problem. Until then, the places where I had grown up and had gone to university were wide open areas. The photographs I had taken during my student days consisted of a simple form or building located in a wide, flat area which I took from a distance. The horizontal photographs I shot had a large expanse of sky in the background. I liked the simplicity of how these photographs appeared. But when I walked around the streets of Tokyo, it was hard to come across wide open areas or forms that were distinct. The spaces in Tokyo are cluttered and narrow, and walking there my view was always obstructed by numerous lines and planes. In Tokyo it seemed impossible for me to take the same kind of photographs I had been used to, causing me to feel a bit despondent.

Feeling that I couldn’t take the type of photographs that I wanted to in Tokyo, my longing for wide open places became stronger. I began to return to my hometown in Iwate. There, my feet turned toward the cement factory I had felt attached to during my high school days. One day, dissatisfied with just gazing at the factory from the outside, I took courage and knocked on the door of the office and asked if I could see inside.

In most cases, cement factories are located near limestone quarries where the raw material is mined. The employee who kindly showed me around the factory asked if I would like to see the quarry. That was the first step in my series of photographs on lime works, which has continued for twenty years (see fig. 2).

2. Naoya Hatakeyama, Lime Hills #23514, 1988, printed 2002; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Kurenboh Collection; © Naoya Hatakeyama

My fascination with the appearance of limestone quarries led me to contact the limestone mining industry association in Tokyo. With the association’s cooperation, I spent about eight years visiting many mines all over Japan, from Hokkaido in the north to Okinawa in the south. During that time I learned to take architectural photographs with a large-sized camera, and I visited many cement factories.

Finally, in 1996 my book on this work came out. During the eight years of working on this project, the way I looked at Tokyo, the city where I lived, gradually changed.

Flying back to Tokyo from the lime works, at times the aircraft would circle over Tokyo. Viewed from the sky, Tokyo looks like a flat plane inlaid with fine-grained stones. I immediately associated this with the rocks that I had seen at the limestone quarries. In fact, in order to build the buildings and roads of the city, limestone is dug out and turned into concrete; so, viewed on a massive scale, it is natural that the texture of a city is like the texture of rocks.

When I was taking photographs at the limestone quarries, I often heard the workers express distrust of photographers. Some photographers would take pictures of the quarries to expose them to the media as sites of the destruction of nature. Whenever this happened, the workers felt despair. When we see a green mountain destroyed and the large hole left behind, it is understandable that a feeling of bitter regret wells up in our hearts. But do we usually look at the destroyed mountain and think of where the rocks that filled the large hole are now?

The relationship between society and nature is, in a word, complex. For instance, if we think about who or what corporation is to blame for global warming due to carbon dioxide emissions, anyone can see that the answer is not a simple one. Furthermore, nature as an environment for existence is not necessarily the same as nature that can be viewed for its aesthetic qualities. But we often confuse these two. That is, in general we think of nature as something beautiful, but we often forget that our sense of beauty itself contains a very artificial aspect cultivated within our history of literature and art. I don’t know how many times larger the total area of golf courses made by cutting down forests is compared to the total area of lime works in Japan. And yet, people in urban areas go by car to golf courses on their days off to “enjoy nature.”

Although the problem is a complex one, if we consider it too complex to deal with and give up on discussion and political solutions, it is certain that the destruction of nature will worsen. It is not overstating the issue to say that we all live with this dilemma.

From the beginning, I did not intend my photographs of the lime quarries and factories to be a way of giving a simplistic message of “the reality of the destruction of nature.” Limestone is used to make the cities, buildings, and roads where we live. We are the ones who are gouging the hillsides. During the eight years of this project, I took my photographs with these thoughts in mind.

I came to think about the far-off limestone quarries even as I lived in Tokyo and gazed at the streets there. I began to feel a connection between the city and the lime works. I think a sense of connection is a wonderful thing. Connecting with a place or connecting with people is what allows us a sense of reality and a confirmation that we are alive.

When I began my work at the mines in the 1980s, the focus of my interest was only in the landscape. I went to the mines to take landscape photographs. Often, during my shoot, a staff worker would say, “We’re going to blast so you have to evacuate.” From a hilltop far away, I could see the working face suddenly swell, and a little later hear a blast, while shattered rock scattered in the smoke. I spent much time idly watching this from a distance.

Eventually, I felt the urge to observe more closely the way the rocks shatter and fall. I was finally able to do this in 1995. I had no desire to shoot this with a telephoto lens from a distance. As the distance between the camera and the subject becomes evident in the photograph, it was obvious to me that it would give the impression of having been taken from a safe place.

I wanted to get close, but there was no way that the workers at the site would allow this. First of all, the danger to life was too great. Even being struck by a small rock could cause instant death. I then thought that I could be at a distance, while setting my camera up close. Initially I tried this using a large camera. But I found I couldn’t use a fast shutter speed, and I could only take one photograph with each chance. So I decided to use a small camera with a motor drive. To operate this, I first tried an infrared receiver and a flash; but then I heard that Nikon had a controller with an FM radio frequency. When I tested this, I found that I could easily operate the camera from quite a distance; so I have been using this method.

The problem was how to persuade those in charge at the mines. When I proposed that I would make an album of the sequence of photographs and present it to them, I received permission to photograph from several mines where I had good relations. They had no way of seeing how the rocks were blasted from up close, so I think they were interested from a technical perspective.

Nearly every day, there are two to three blasts in mines across Japan, but no person had ever stood in the place where my camera would be placed. This place could be likened to a “secluded area” that no one had stepped into throughout history, or a planet where an unmanned probe had landed.

Each time, I asked for advice on where to place my camera from the mine’s blasting technicians. From their location on top of a bluff, they would show me where I should put my camera so it would be close yet not be destroyed. I was moved by their ability to imagine in their minds how two thousand tons of rock would break apart and then give me accurate advice. From having worked with rock for so many years, they had gained a vision that I could never imagine. One could say that they were in dialogue with nature in the form of the rocks.

3. Naoya Hatakeyama, Blast #12115, 2005; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Kurenboh Collection; © Naoya Hatakeyama

On one hand there are artistic people who see nature with an aesthetic sense; and on the other hand there are technical people who accumulate understanding and wisdom by touching nature. Leaving aside the issue of which type is more peace-oriented, which type do photographers fit into?

I recall that in the early history of photography there was a person who recognized the importance of the word nature. That was William Henry Fox Talbot of Britain. As you know, he called photography the “pencil of nature”: photography was nature taking up a pencil and drawing a picture. This phrase has sweet echoes of the far ancient past when ars (art) and techne (technology) were unified.

When we compare “nature” with “photography,” we in modern times tend to have our vision absorbed only by the nature that is outside the photograph, as its subject. We tend to forget that nature exists within the photograph as well. Nature inhabits the medium of photography itself. I do not want to forget our forebears who were aware of this.

If photography is nature, there is a possibility for a unique ecology to exist. Isn’t the activity of twentieth-century modern photography, promoted in the main by America, an investigation into the mutual relationship between photography as environment and humans?

It might be an overstatement to say that photography is facing an “ecological crisis” due to the massive digital revolution taking place today. Anyone can see that the future environment of photography will be quite different from taking up the “pencil of nature” of the past. In this age, when photographic paper and film is disappearing and countless images taken with mobile phones are instantaneously sent around the world, the meaning of “nature” in photography is definitely beginning to transform.

This summer I took a photograph of a bird. It might be more accurate to say that it appeared in my photograph, rather than that I took it. You can see the small figure of the bird at the left in the sky. This bird accidentally entered the frame and, surprised by the blast, flew away. It felt to me as if “nature” was fleeing. From what? Perhaps from something human.

The enormous power of humans obscures “nature” for an instant, but when the exercise of that power settles down, “nature” reappears as if nothing had happened and goes off to another location. The frame doesn’t move, the human world remains fixed, while “nature” moves out of the frame as if to escape trouble. I may be reading too much into it, but this is what I felt on seeing this photograph.

Modern photographers have poured their effort and passion into mediating and stimulating the dialectical relationship between nature internal to the photograph and nature at the other end of the lens. Those of you gathered here are familiar with this, so I don’t need to discuss this further.

And now we are in the twenty-first century. With the development of digital technology, the nature inherent in photography will move to the next phase. As this doesn’t look like it will be of “nature,” it will not be a very comfortable place for someone like myself. But even with digital technology, as long as it is “technology” there must be a point of contact with “nature,” with the birth of a new form of dialectic with the outer world.

In closing, I wonder how much material my photographs were able to give you in thinking about the words change, nature, man-made, landscape, and inhabit. And, to you who are in San Francisco, I wonder how much you noticed the influence of American photography of the latter half of the twentieth century in my work.

I would be very happy if my talk today might be of some reference as you continue your practice of photography from tomorrow. I don’t know if I will be able to report to you on my work again ten years from now. But I will dream of that occasion as I engage in my projects.