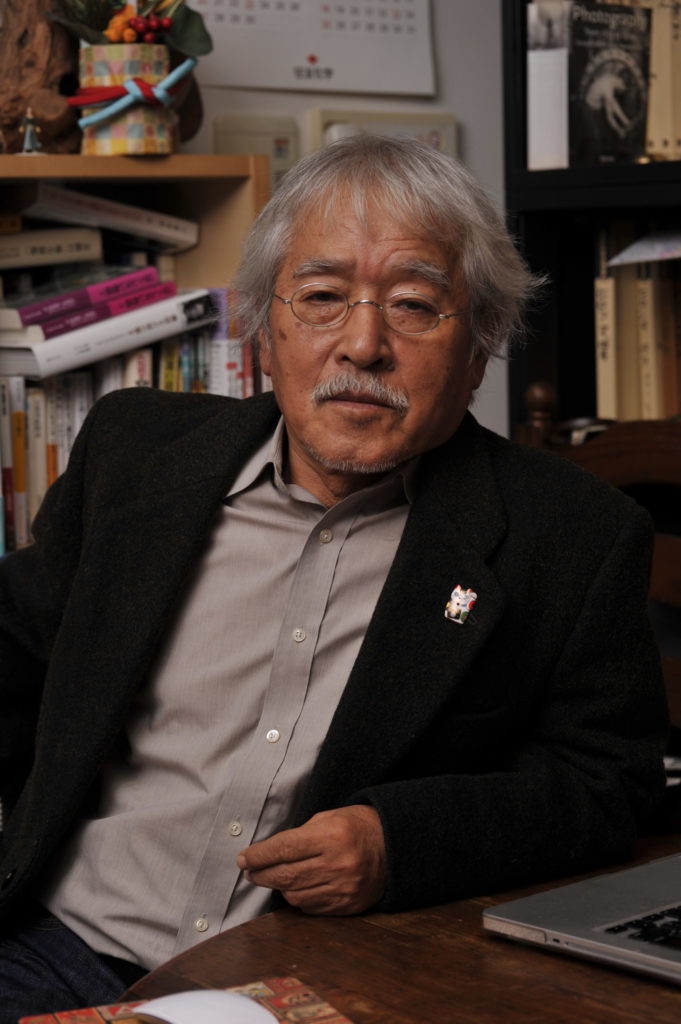

Artist

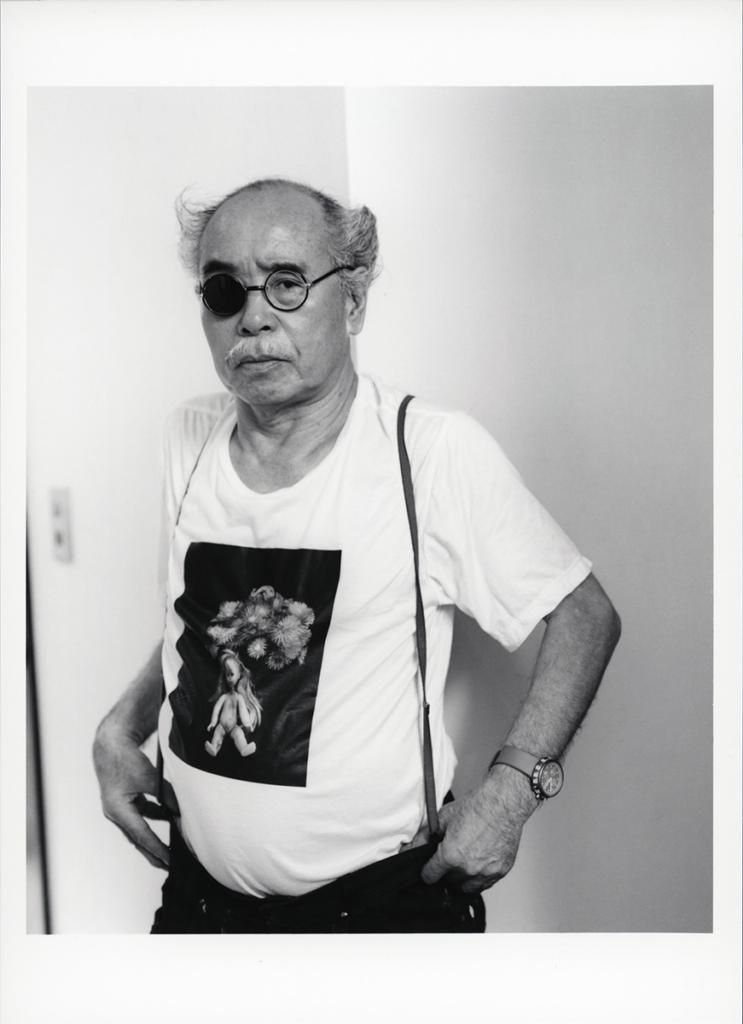

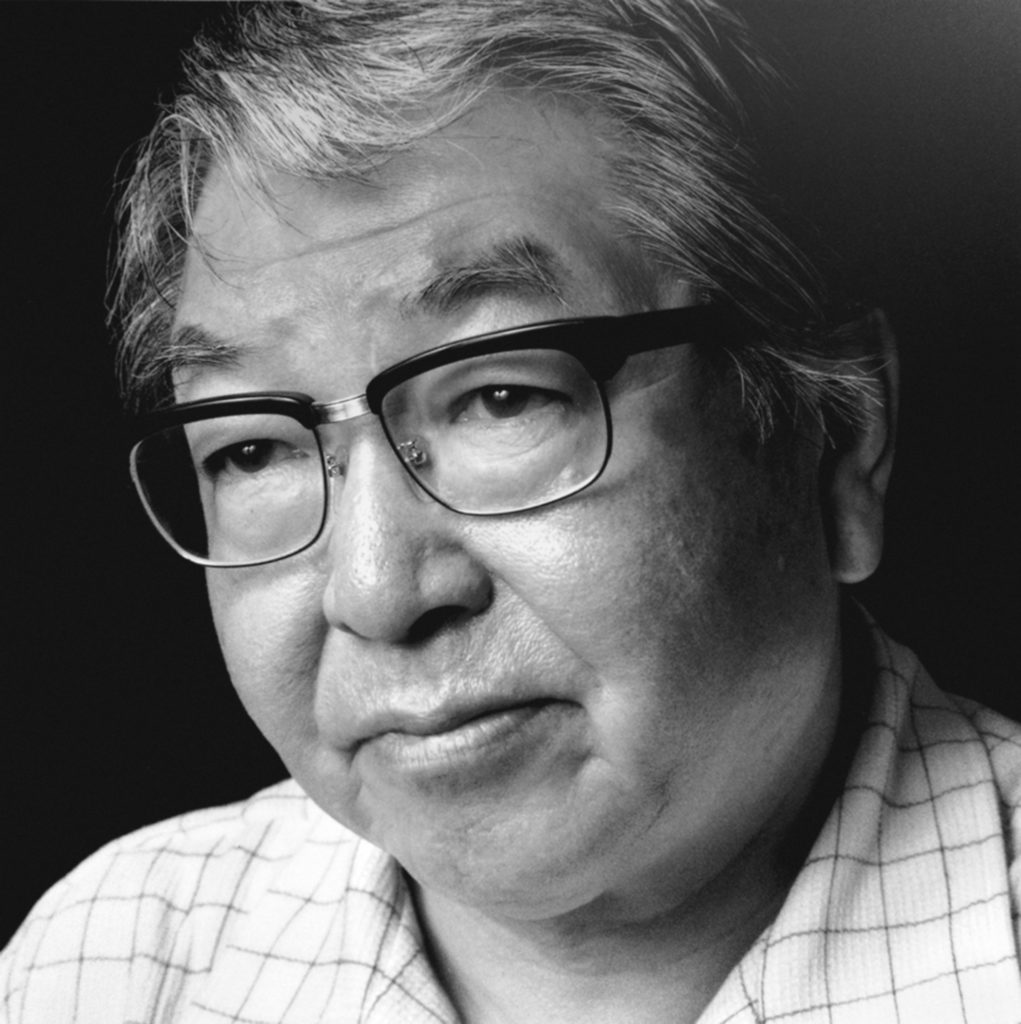

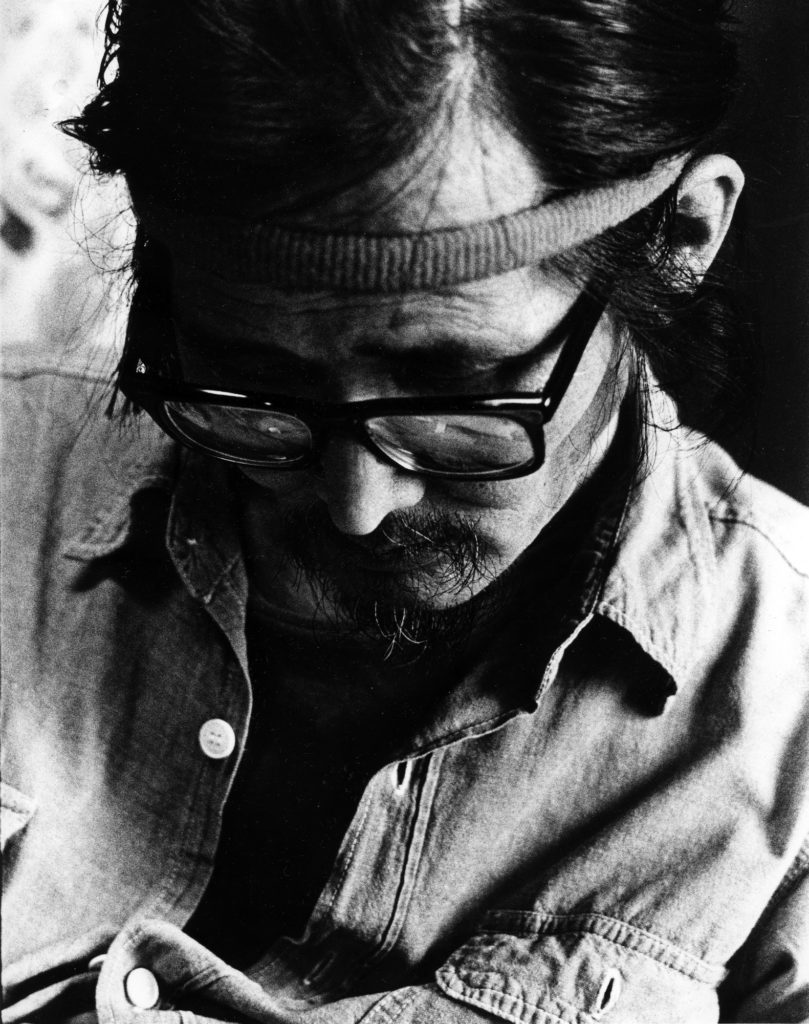

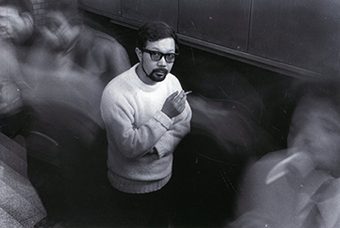

Daido Moriyama

Japanese

1938, Ikeda, Osaka

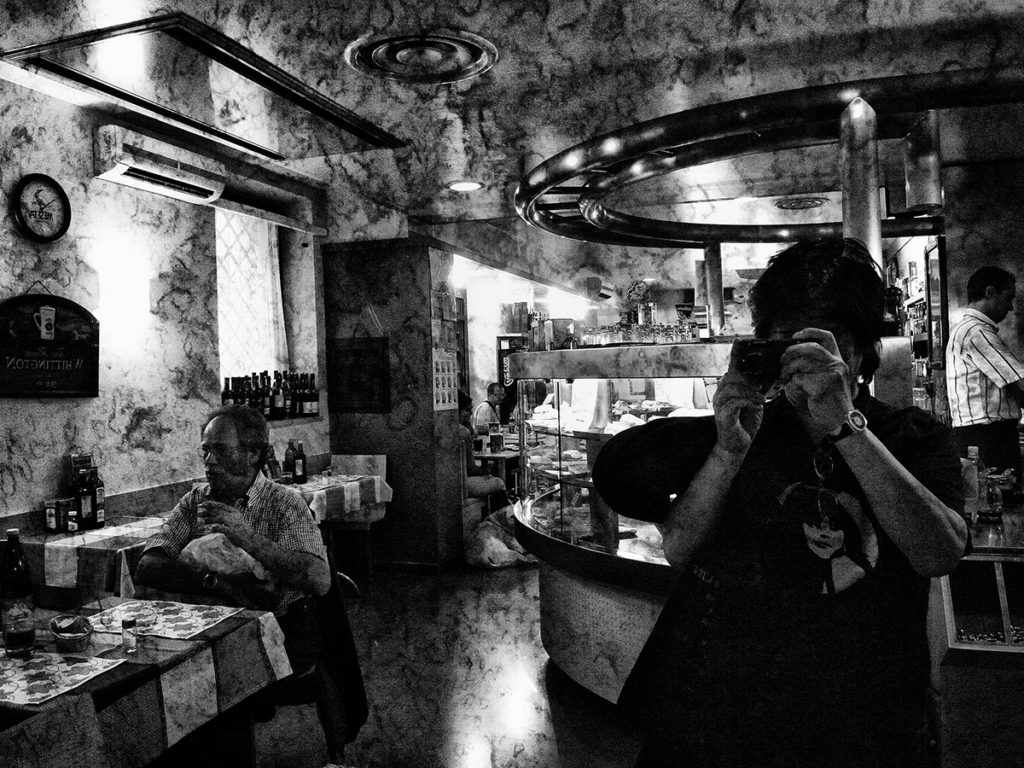

A seminal photographer of lyrical, expressionist sensibility, Daido Moriyama (b. 1938) has restlessly portrayed the emotional condition of everyday postwar Japan. He belongs to the generation who matured in the decades following Japan’s surrender—who lived in urban centers and experienced the country’s submission to occupation and political pressures by its “liberators,” as well as its emergence as a vibrant economy. These and other factors stimulated a period of radical art-making. “Chaotic everyday existence is what I think Japan is all about,” he has said. “This kind of theatricality is not just a metaphor but is also, I think, our actual reality.”[1] Moriyama worked as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe while the older photographer made his portrait series of the novelist Yukio Mishima, pictures of theatrical sexuality. Later he saw work by William Klein and Andy Warhol, whose photographs, provocative and raw, exposed a society of vibrant estrangement in New York. Moriyama responded most of all to the vitality and fleshy dissipations he observed at the American bases near where he lived, in Zushi, then teeming with American servicemen fighting the Vietnam War. He was attracted to the culture there: to the jazz music, to the honky-tonk joints and the heterogeneity of their clientele, and to the exuberance of the soldiers. The nonpolitical Moriyama found in the rich complexities and dark ambiguities of the times his special subject.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Moriyama contributed regularly to camera magazines published for the amateur, especially the important Camera Mainichi, producing pictures for these publications that were essentially poetic rather than journalistic. His subjects included popular entertainment and the experimental theater of Shuji Terayama, as found in the pictures of his first book, Japan: A Photo Theater (1968). An admirer of Jack Kerouac, he hitchhiked throughout Japan or found drivers willing to take him on the new highways at all hours of the day and night, stopping at deserted cafes and photographing through car windows, inspired by Kerouac’s On the Road. These photographs were published serially in Camera Mainichi beginning in 1968, but he would continue this restless movement around the country as well as in city streets in the decades that followed. Through an introduction from his friend Takuma Nakahira, Moriyama participated in the experimental magazine Provoke (1968–69), maintaining his apolitical stance within this highly political group. Experimenting boldly with cropping and pronounced grain, he also took pictures of pictures and reframed them, as in the Warholian series Accident (1969), a group of which are based on a traffic safety poster. In 1974 he produced a book of Xeroxed photographs of a 1971 visit to New York, calling it Another Country in New York, after another favorite author, James Baldwin.

Moriyama’s work is best understood in the context of the deeply divided politics of the times, especially the protests surrounding the renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in 1970, as well as the subsequent decline in political antagonism between the two countries and the rise in consumerism. For Moriyama, this was the beginning of both a highly productive period and, by the mid-1970s, a time of personal instability. In 1972 he published two important books, Hunter and Farewell Photography, and launched the small photographic magazine Record. Hunter contains some of Moriyama’s best-known pictures, printed in stark, gripping contrast. Farewell Photography is a gorgeously experimental production that continued his interest in Warhol-inspired printing; many of the pictures are blurred and highly cropped, and their subjects, from a blank television screen to a looming helicopter suspended in midair, are often almost unrecognizable. The mood is tragic and nihilistic. Appropriately, the book’s introduction is a conversation with his friend Nakahira, who would suffer a severe case of alcohol poisoning soon after.

It took some years for Moriyama to evolve out of this intensity. He began to visit the Japanese countryside, where he produced The Tales of Tono (1974, published 1976), a strange and disorienting series of pictures that reach into preindustrial rural Japan but are not escapist. That year he began to receive attention outside Japan: his work was included in New Japanese Photography, the 1974 exhibition organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which traveled to SFMOMA the following year. This success coincided with the recognition of photography as a particular form of artistic expression in Japan, celebrated in the exhibition Fifteen Photographers Today at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Moriyama has continued to work experimentally and to rethink his earlier projects, often incorporating older work with more recent pictures in expanded book formats. The photographs in Light and Shadow (1982), produced after a long period of inactivity, are imbued with a new, even blinding clarity. In 1990 he published Lettre à St. Loup, in which he describes the first photograph, made by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce in 1827, as deeply important to him; Niépce’s photograph is a grainy, confusing, yet eloquent picture of the passage of the sun from one side of a courtyard to the other.[2] More recently Moriyama has taken up color again, which he employed infrequently in the 1970s. These new color pictures, made with a special camera, have injected a directness, even a sense of normalcy, in contradistinction to the rawer work of the earlier years.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

- Daido Moriyama, letter to Sandra S. Phillips, n.d. [1998]; quoted in Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1999), 32.

- Daido Moriyama, “That Summer Day in St. Loup,” in Lettre à St. Loup (Tokyo: Kwade Shobo Shinsha, 1990), n.p.