Artist

Rinko Kawauchi

Japanese

1972, Higashiomi, Shiga Prefecture

In contrast to photographers working in the dark and frenetic style developed during the Provoke era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Rinko Kawauchi (b. 1972) has pursued a more restrained and lyrical aesthetic over more than two decades. The most quotidian objects and occurrences are transformed through her lens into sublime images that frequently highlight the ephemeral, fragile, and even sinister nature of everyday life.

Kawauchi studied graphic design and photography at Seian University of Art and Design, Otsu, Japan, and worked in the commercial and advertising realms upon graduating in 1993. She shifted her focus to fine art a few years later and quickly gained international recognition—including the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award—after the simultaneous release of a trilogy of photobooks in 2001: Utatane, Hanabi, and Hanako. Almost entirely devoid of text, these volumes rely on the power of the images speaking to one another across the pages to create their narratives. Common scenes such as a curtain blowing out an open window, soap bubbles gathering in a sink drain, or a young child jumping rope seem to reflect a deeply personal and idiosyncratic experience of the world, as well as a dedicated practice of intense looking. The muted color palette in Utatane, which has become the artist’s trademark, produces a dreamy and ethereal atmosphere that complements her sparse and mysterious compositions. Similarly, Kawauchi renders the explosive fireworks in Hanabi as quasi-abstract studies that are seemingly more concerned with the effects of light than with figuration.

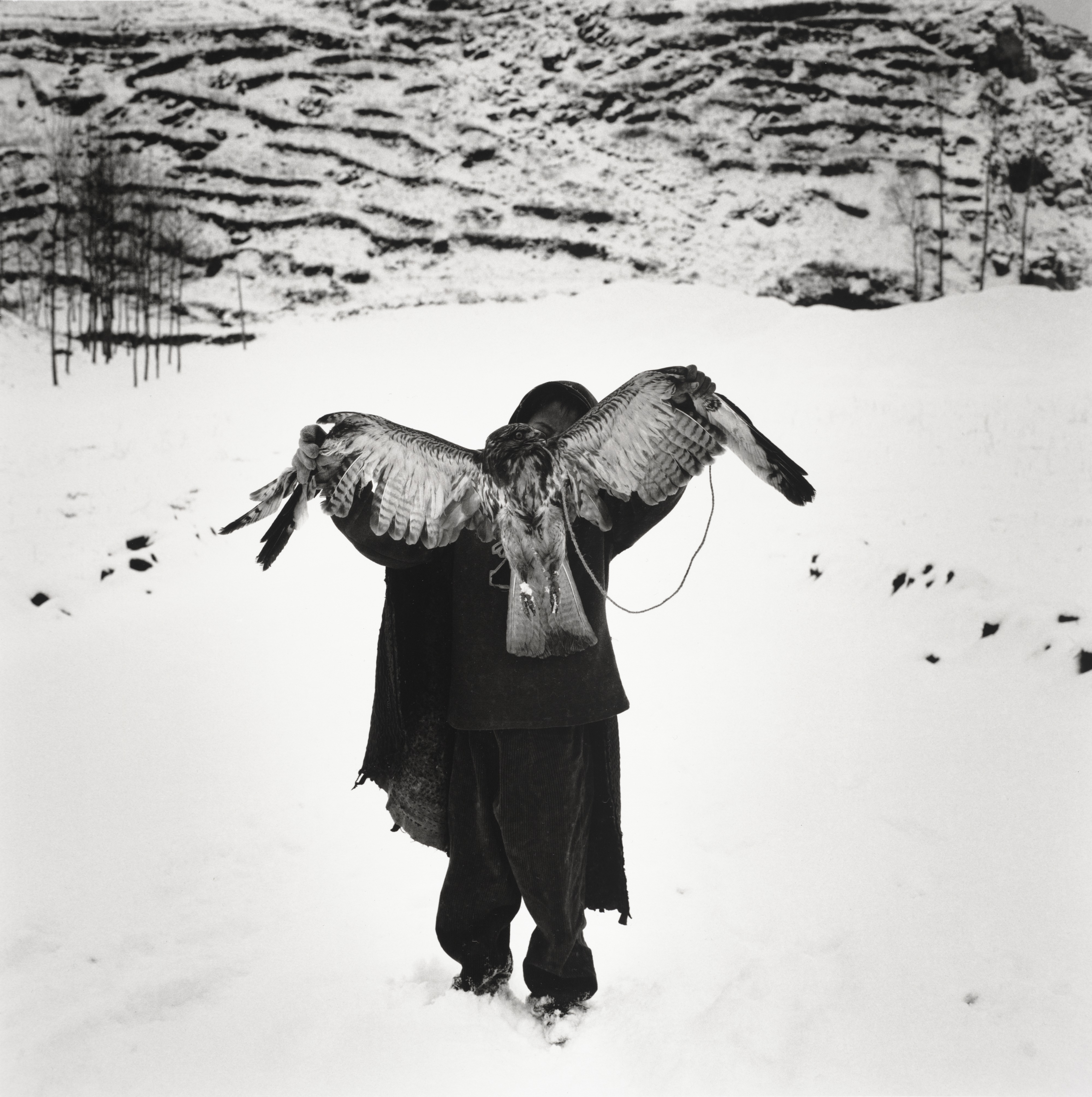

Kawauchi’s poetic imagery has continued to develop in subsequent series. While the eyes, the ears (2005) comprises the same types of quiet photographs found in her earlier bodies of work, it juxtaposes the pictures with short—though equally obscure—verses of the artist’s own invention. Her 2013 project Ametsuchi ventures even further into the metaphysical realm. Focusing on a landscape Kawauchi first encountered in a dream, it captures the centuries-old process of noyaki, a yearly controlled burn of Japan’s Aso countryside in order to maintain and refresh the grasslands for grazing animals. Though the ultimate outcome of the procedure is regeneration, Kawauchi’s photographs of the hills ablaze are decidedly melancholic. Ametsuchi may seem like a departure from the tranquility of Utatane, but both reveal an enduring interest in what the artist calls “the flow and cycle of human practices.”[1]

— Matthew Kluk

Notes

- Rinko Kawauchi, in “Rinko Kawauchi Contemplates the Small Mysteries of Life,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, March 2016, video, https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/rinko-kawauchi-contemplates-small-mysteries-life/.