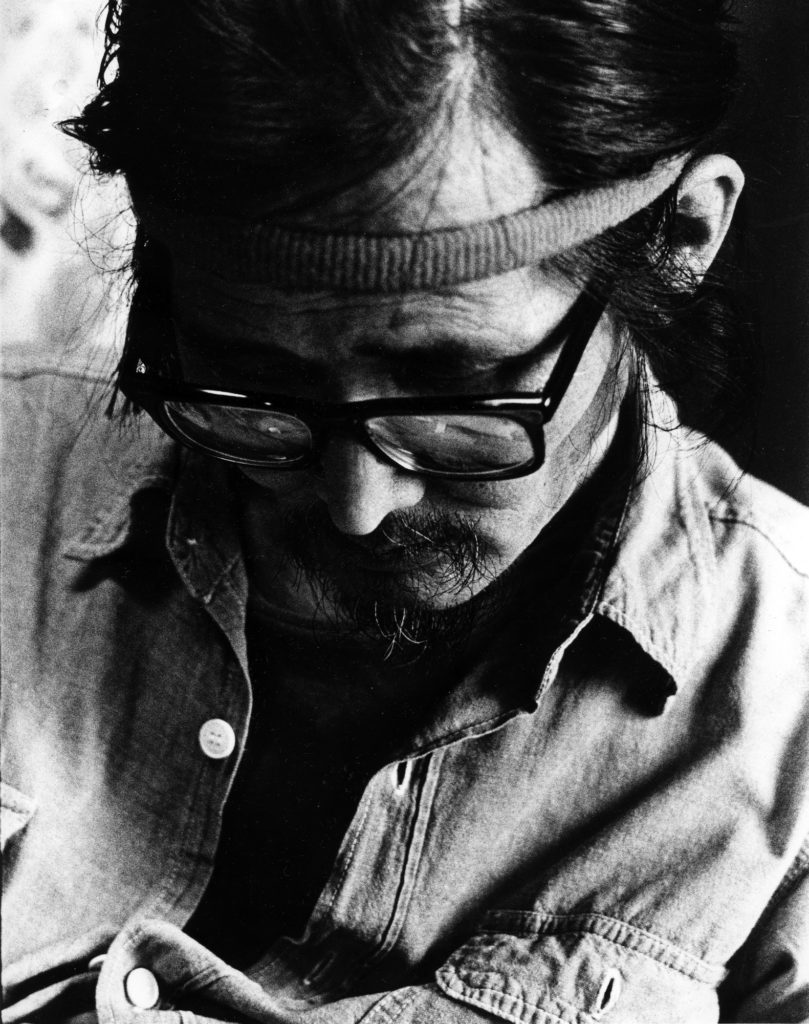

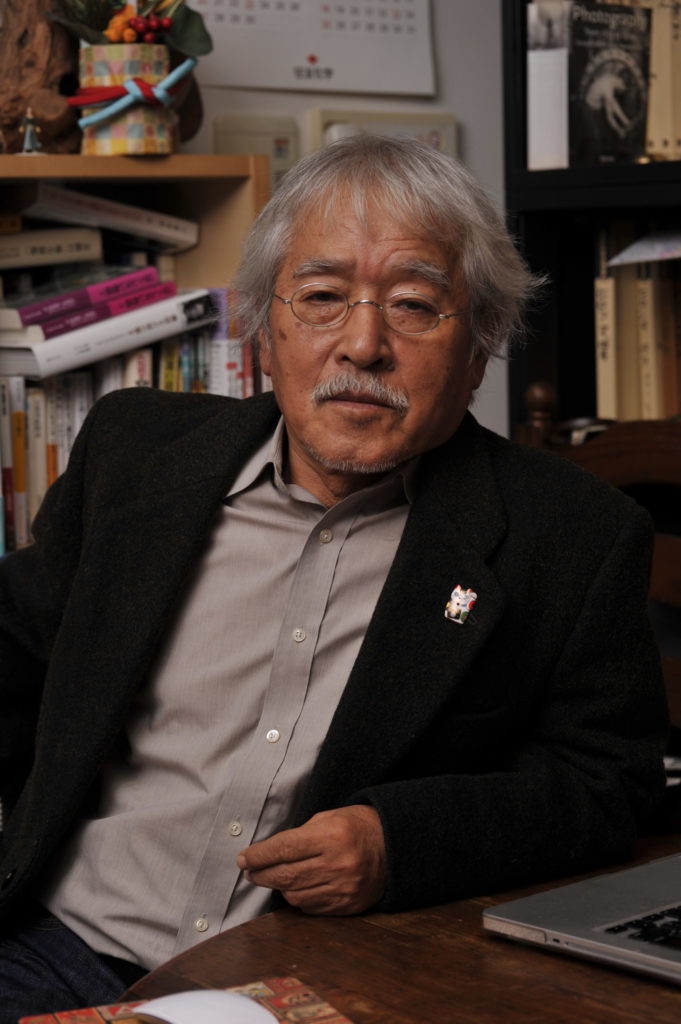

Artist

Miyako Ishiuchi

Japanese

1947, Kiryu, Gunma Prefecture

Raised in Yokosuka, home to the largest American naval base in Japan at that time, Miyako Ishiuchi (b. 1947) was taught while she was growing up to fear the city’s American section, especially the bar district where soldiers fraternized with Japanese women. Reports of violence there were frequent. She left Yokosuka as soon as she could–in 1966–to study design at the prestigious Tama Art University in Tokyo. There she participated in student protests that closed down the school for almost a year in 1969, part of a wave of student demonstrations across Japan, demanding university administration reform and fighting American influence in the region. She was also involved in the burgeoning women’s movement and formed a women’s group with two fellow students.

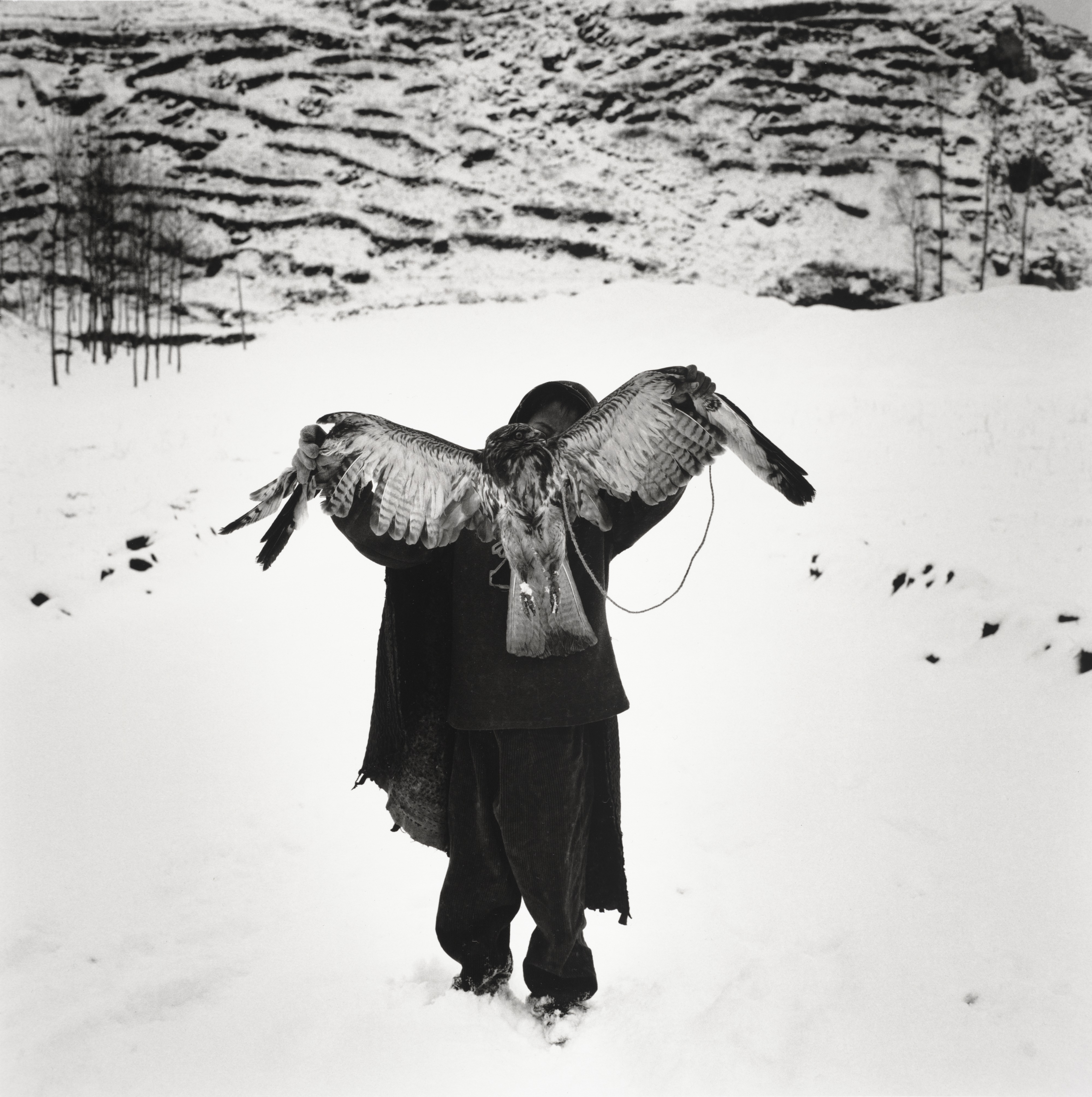

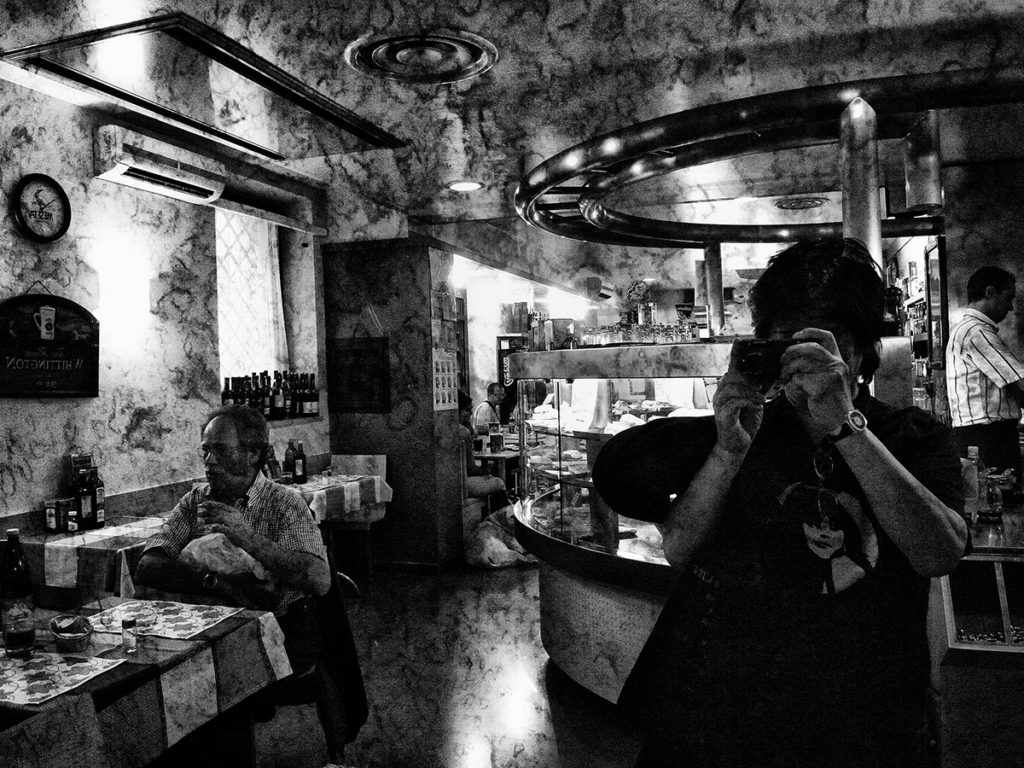

Ishiuchi initially worked in textiles, but by 1975 she was actively making photographs. She found her essential subject by confronting her past: in 1976 she returned to Yokosuka to photograph its American military population, then in decline with the end of the Vietnam War. The pictures she made there were, she said, “coughed up like black phlegm onto hundreds of stark white developing papers.”[1] Persuading her father to give her funds he had set aside for her dowry, she published a group of these photographs in her first book, Apartment, in 1978. Two more books of her Yokusuka pictures followed: Yokosuka Story (1979) and Endless Night (1981). In the latter, she focused on the crumbling bars and brothels that had so distressed her, now abandoned and being demolished. To firmly acknowledge the centrality of Yokosuka’s heritage for her, in 1981 she rented a cabaret in the city to hold an exhibition of this work. She later commented: “The photograph exhibit took place, as though in revenge, there in Yokosuka which was in America, in America which was in Yokosuka, a town which thrived from what two wars yielded, on a street now become a pathetic sight to see.”[2] She would stop photographing Yokosuka in 1990.

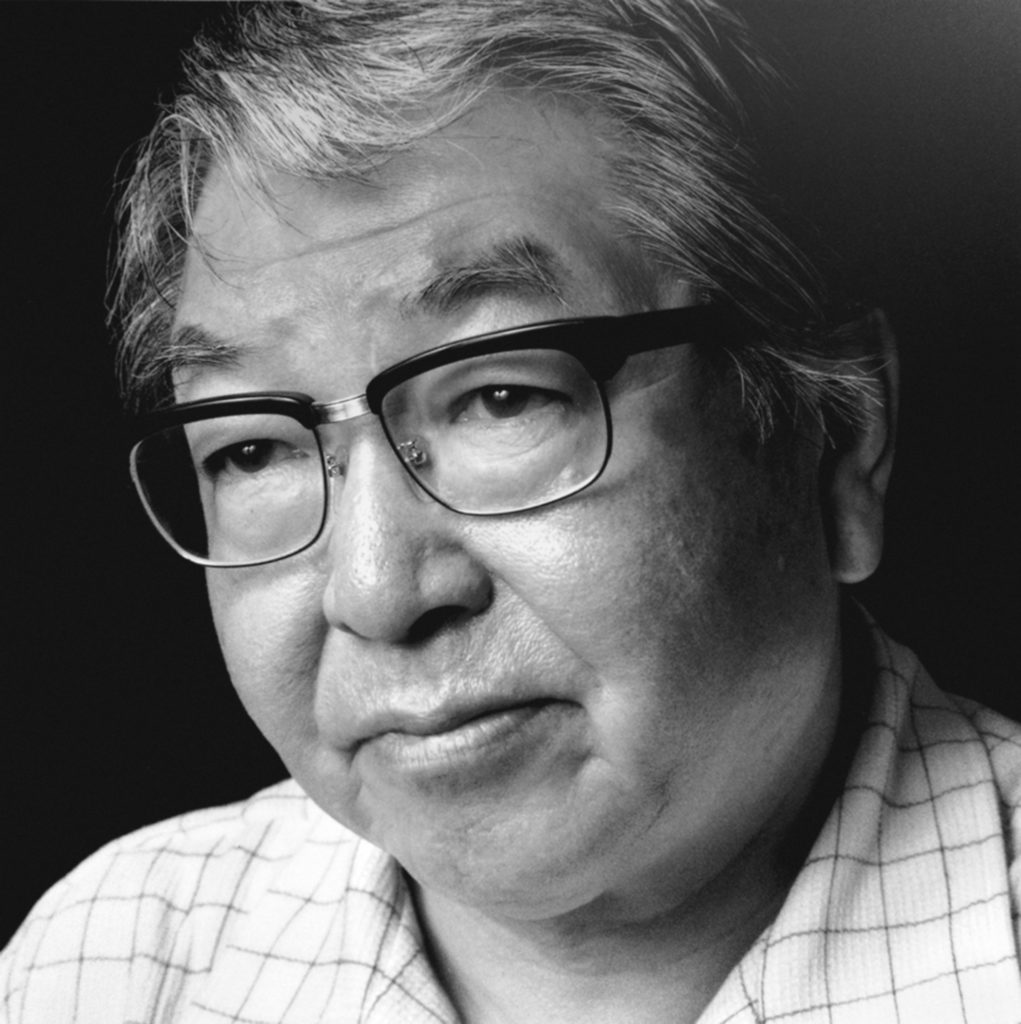

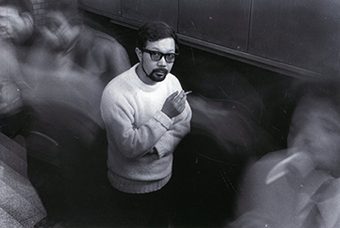

Ishiuchi’s unique perspective on the American presence in Japan—reflected in distinctively quiet but also emotionally riven photographs—drew the attention of Shoji Yamagishi, renowned editor of the journal Camera Mainichi. Ishiuchi was the only woman whose work he included in Japan: A Self-Portrait, the 1979 exhibition he organized for the International Center of Photography in New York. Thus introduced internationally, Ishiuchi’s particular vision drew the attention of other Japanese women photographers, especially Asako Narahashi, with whom she would later create the photographic magazine Main (1996–2000). In 1984 Kyoko Yamagishi, widow of Shoji Yamagishi, invited her to participate in a project with a large-format Polaroid camera. She used the occasion to photograph members of her high-school class of twenty years earlier, in the series Classmates (1984). This experience encouraged her to expand her subject matter in a radically new direction. Rather than photographing the place of trauma, which was Yokosuka for her, she photographed its effects, first on the body and later on its second skin, clothing. The project 1∙9∙4∙7, begun in 1987 and published in book form in 1990, involved the close-up examination of the hands and feet of women born, like her, in 1947. Carefully detailing what the bodies of women her age—neither young nor yet old—looked like, she identified her subjects only by birth year and profession. This intensified concentration on the body’s surface led Ishiuchi to her subsequent series, Scars (1991–2003). She has likened these marks on the human body to photographs themselves: “When I first encountered the scar, I reflected on photography. . . . While a person hopes to remain unblemished through life, all must sustain and live with wounds, visible and invisible . . . an imprint of the past, welded onto a part of the body.”[3]

By 1999 Ishiuchi began to photograph her mother, concentrating on her scars and other details of her aged body. This series of pictures would continue after her mother’s sudden death the next year, when Ishiuchi turned to her mother’s clothing and other personal effects, producing monumental pictures of items such as used lipsticks and worn undergarments, rendered like cobwebs with wear. Mother’s was presented in the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2005. More recently Ishiuchi has photographed clothing found after the atomic bomb explosion at Hiroshima, spreading the garments on light boxes to suggest the personality of the wearer. Clearly used and often handmade, the clothing items embody their traumatic history but are photographed in a way that expresses a specific personality, even a spiritual presence.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

- Miyako Ishiuchi, Yokosuka Story (Tokyo: Shashin Tsushinsha, 1979); quoted in Amanda Maddox, “Against the Grain: Ishiuchi Miyako and the Yokosuka Trilogy,” in Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015), 23.

- Miyako Ishiuchi, Yokosuka Again, 1980–1990 (Tokyo: Sokyu-sha & Mole, 1998); quoted in Maddox, “Against the Grain,” 28.

- Miyako Ishiuchi, Scars (Tokyo: Sokyu-sha, 2005), n.p.